Louisa May Alcott: 10 Fun, Little Known Facts

IN FEBRUARY, I visited the Orchard House in Concord, MA, where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women behind the second-floor windows on the right. The year ... 1868, the same year my great-grandmother Isabella Stewart was born in Denholm, Scotland, clear across the ocean. Such different lives! Granny lived in the heart of the Scottish borderlands—daughter of a poor agricultural laborer on Hall Rule Farm, where barefooted she hoed onions to help support the family. Louisa May Alcott was already an established writer by the time Isabella came along, and although she didn’t hoe onions to support her family’s crippling poverty, her prolific writing made her the primary bread winner.

She was just fifteen when she vowed to pull her family out of poverty. “I will do something by and by. Don’t care what, teach, sew, act, write, anything to help the family before I die, see if I won’t!”

Her first publication came out in 1852, the same year Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared. “Sunlight,” written under the name of Flora Fairfield, was printed in Peterson’s Magazine. Her first book, Flower Fables, fairy tales written to amuse Ralph Waldo Emerson’s daughter Ellen six years earlier, was published in 1854 under her own name. Her first novel came out in 1856. Then came gothic thrillers — “blood and thunder tales” as she liked to call them — with names like Pauline’s Passion and Punishment and A Long Fatal Love Chase, these written in secret and under a pseudonym to keep from staining her rising reputation. By the time my great-granny was born, Louisa was writing up to fourteen hours a day without taking a break, without eating, changing hands right to left and back again so she could keep on when they cramped and even bled, spewing out Little Women in just six weeks.

Her book we know, her life not so much. I think what we don’t know almost as fascinating than what we do know. She was born into a Christian family who acceded to the principles of Transcendentalism—a belief calling for Duty and Responsibility because God was in all and was all. Always curious about women of faith, my visit to Orchard House led me to at least ten little known “Fun Facts” about this best-selling author.

ONE: Louisa didn’t want to write Little Woman, a story that’s never gone out of print, even after 150 years. Her publisher, Thomas Niles of Roberts House, wanted a book about girls. A tomboy, Alcott was heartily disinterested. Niles begged, he bribed. No, she wouldn’t do it. Then her father asked Niles to publish his own book on philosophy. “Only if,” said Niles, “you can get that daughter of yours to write a book about girls.”

And so Alcott sat down and banged out Little Woman at the little shelf-desk her father made for her in front of the windows, a story loosely based on her childhood with sisters Anna (Meg), Lizzie (Beth), and Abigail May (Amy). “Marmie, Anna, and May all approve the plan,” Alcott wrote in her journal at the time. “So I plod away, though I don’t enjoy this sort of thing. Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters; but our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting, though I doubt it.”

TWO, Niles wanted her main character Jo to marry Laurie next door. (In reality, Henry David Thoreau lived next door!) NO! Why must all women marry? Louisa bewailed. “I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe.” In a journal entry, she wrote: “Girls write to ask who the little women will marry, as if that was the only end and aim of a woman’s life. I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please anyone.”

“So come up with a character,” insisted Niles, “Jo can marry.” Push came to shove. In the end, Louisa gave us the disconcerting downfall of the novel—Mr. Bhaer. Movie producers ever since have had a hard time creating motivation or reader identification when it comes to the man Louisa forced Jo fall in love with and marry. Nonetheless, the book was an instant success, and as the royalties rolled in so did the debts roll out; some, like her sister’s Lizzie’s medical bills prior to her death ten years before, paid off at last. “Every penny that money can pay—and now I feel as if I could die in peace,” Alcott wrote. Before long, her biographer Harriet Riesen claims she was making, in today’s value, $2,000,000 a year.

THREE, prior to Little Women when the family was so destitute, it was Ralph Waldo Emerson who helped them buy Orchard House in Concord, in which they lived for 20 years. A relief to Mrs. Alcott, who’d moved twenty times in thirty years. Her husband, Bronson, was a visionary educator who believed children should enjoy learning, that boys and girls should learn together, that nature walks and visiting museums should augment textbooks, that children should be part of the process, talking and asking questions, making their own observations, and that all children, black and white, should have the right to an education. He is the one to invent recess, allowing children time to go out and play. Today this is a basic minimum; back then it was revolutionary, and people withdrew their kids. Home buying then was not an option for this desperately poor family. But Bronson hob-knobbed with men like Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other great writers of the Transcendentalist movement; and Emerson (who agreed with Bronson’s philosophy of education and even taught with him, and even taught his children, including Louisa) paid the larger portion of $945 in 1857 to help purchase the 12-acre apple orchard and home already 200 years old.

FOUR, despite her family’s poverty, Alcott had connections that gave her an exemplary access to the larger world and gave her role models of passionate social consciousness. She had access to Emerson’s library, studied botany at Walden Pond, fraternized with Frederick Douglas, Julia Ward Howe, and Margaret Fuller. All the top thinkers of the day gathered at Orchard House. Such thinking was her bread and butter and on this she grew into a woman far more revolutionary than Little Women ever hints at.

FIVE, she was an abolitionist. Her father, in 1850 and along with Frank Lloyd Garrison, founded an abolitionist society in their home two years before Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin took the country by storm. At “Wayside,” the Alcott home in the 1850s, the house became a way station on the Underground Railroad. Also at Orchard House seven years, the family hiding escaping slaves. Her mother once hid a fugitive in her oven. Louisa churned out articles in abolition magazines and newspapers.

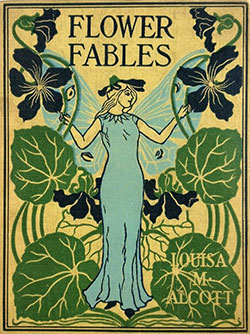

SIX, unlike in Little Women where Jo’s father went off to the Civil War as a chaplain, in reality it was Louisa who went—as a nurse. Six weeks later, she unfortunately contracted typhoid and pneumonia, a double whammy from which people stronger than her died. Doctors treated her with the standard of the day, calomel, rich in mercury. Nip and tuck, she very nearly died. Weak and still fevered, Bronson went to fetch her home. Still deathly ill, the doctor continued with the mercury and ordered her head shaven—to bring the fever down, he said. At last she recovered, but only to some degree. She was never the same. But she got so she could sit up at the shelf-desk her father had made in front of the windows, and there she wrote Hospital Sketches, a popular book in 1863 that allowed her audience to see the “true war.” The mercury poisoning, though, left her with what we now know was a weakened immune system, causing unexplained skin rashes, vertigo, hallucinations, crippling, chronic joint pain, and turned her complexion to ash. But of the brief six weeks, she said: “I shall never regret the going, though a sharp tussle with typhoid, ten dollars and a wig are all the visible results of the experiment; for one may live and learn much in a month … My greatest pride is that I lived to know the brave men and women who did so much for the cause, and that I had a very small share in the war which put an end to a great wrong.”

SEVEN, she was a suffragette. In the 1870s, during her fifties, she wrote for a women’s rights periodical and went door-to-door to encourage women to vote. In 1879, when the state passed legislation allowing women to vote in local elections pertaining to education and children, she became the first woman in Concord to register. Election time, despite the opposition, she joined 19 other women and cast her ballot. “I can remember,” she wrote to Thomas Niles of the struggle, “when anti-slavery was in just the same state that suffrage is now, and take more pride in the very small help we Alcotts could give than in all the books I ever wrote … ”

EIGHT, she shied from all the media attention and retreated from fans flocking to Orchard House. One month, 100 people knocked on her door. To avoid them, she took to masquerading as the maid, the gardener, anything to trick them into leaving.

NINE, she sent her youngest sister, May (Amy), to art schools in London, Paris, and Rome. May became known in her own right, her work selected for the prestigious Paris Salon and attracting attention. It was she who did the sketches for Little Women’s first printing, followed by her own book Concord Sketches. She taught art and sculpture in New York, Boston, and Concord, one her students being Daniel Chester French. He went on to sculpt the famous Minuteman statue and the Lincoln Memorial. Who would ever guess?

TEN, May, married and living overseas, died from childbirth in 1879, the same year Louisa cast her first ballot. On her deathbed, May asked her husband to send “Louisa” to her dear sister Louisa to raise. At nine months old, the baby arrived in Concord and was given her mother’s bedroom, filled with May’s art (Mr. Alcott having encouraged May to draw on the walls), overlooking the apple orchard. Nicknamed Lulu, Alcott raised her until her own death eight years later. Just eight and-a-half years old, the young girl was returned to live with her father in Switzerland.

Throughout her lifetime, everyone regarded the Alcott family geniuses. Driving this was their faith that God put us here to honor the sacredness in all, and of all, which meant active participation in making His world a better place. It’s a telling comment when Louisa wrote to her publishe, telling him she'd trade in all the books she ever wrote to have had the privilege of being active in the abolitionist and suffrage movements.

Louisa May Alcott could spin a good tale; but her lesser known qualities are what inspire me. Her dedication and practical participation in social justice is, in my book at least, what makes her so legendary. I suspect in God’s book too.

She died March 6, 1888, at 55 years old from a stroke. The same day my great-granny Isabella married my great-grandfather Walter Goodfellow. It was no ordinary wedding. My granny was 3 months pregnant—raped by her stepbrother. My kind granddad had beeen courting her and walking the 6 miles between Denholm and Jedburg whenever he could, and did not disengage when he learned of the violence. He stepped up to save Isabella from a life of shame. They had nine more children, immigrated to Canada; and today Goodfellow cousins dot the Alberta prairie landscape.

Isabella Stewart Goodfellow and Louisa May Alcott—two women in history whose lives paralleled for exactly twenty years, two women who never met, two women living in two different worlds, geographically and economically—were two different women who, despite their setbacks, lived lives of faith, doing what they could to make their own unique world a better place.