Anne Hutchinson, Colonial America

Colonial Puritans and Anne Hutchison

story adapted from Taming The Dragons: Choices for Women in Conflict and Pain by Brenda Wilbee

BEFORE Anne Hutchinson was born, her father Francis Marbury had been thrown into English prisons three times for his Puritan views. His daughter, Anne Marbury Richardson, must have gotten her steel from him. She needed it, for she ran afoul of the Purtians themselves—in the New World. They held little tolerance for anyone else.

In 1630 the archbishop of Canterbury, England, cracked down on the growing numbers of Puritans. Anne, her husband William, and their several children were among the first to flee this religious intolerance to the New World—where they hoped to find religious freedom. To help pass the time aboard ship Anne took to holding Bible studies for women, her leadership upsetting some of the men. Upon investigation, the men were further upset to find Anne claiming direct communication from God through his Holy Book. Heresy.

Once in Boston, Anne and her husband quickly made a name for themselves. Within months William was a wealthy merchant while Anne became well known for her Bible studies and preaching, which met weekly in their large home across the street from Governor John Winthrop.

Anne developed a loyal following. Not only was she adept at midwifery, nursing, and friendship, she opened new doors of intellectual thought. Husbands even began attending her Bible studies and before long eighty men and women crowded into her home, leaving many more to stand about outside—much to the governor’s growing dismay.

Bedrock to Puritan government was the notion of a pecking order, men at the top. Anne’s preaching and Bible studies undermined that notion. Who was she, a mere woman, to interpret what only men, ministers, could understand? Winthrop sent the senior minister, John Wilson, and his assistant, John Cotton, to question Anne about her theology.

On the basis of that investigation, she was brought to trial in November 1637. When she again declared that God communicated to her directly through Scripture, Winthrop pronounced, “Mistress Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society ...”15

“Why, what is the charge?”

“Say no more. The court knows and is satisfied.”16

Banishment was set for spring and William set off at once to Rhode Island in search of new land. Taking advantage of his absence, the church tried her a second time. Forty-six years old, pregnant with her thirteenth child and in poor health, she was questioned without break for ten hours. Anyone who’s been pregnant, knows this is too long to go without a potty visit. At long last John Wilson the minister announced, “I command you in the name of Christ Jesus and of this church as a leper to withdraw your selfe out of the Congregation.”17

Anne rose and walked stiffly to the Meeting House door. I can see her holding the small of her back, aching and sore, her skirts soiled with urine and possibly feces. But I can hear the ring of conviction in her voice. “The Lord judgeth not as man judgeth. Better to be cast out of the Church than to deny Christ.”18

Anne, nine of her children, and a few loyal followers set out on foot for Rhode Island, covering sixty miles in six days. It proved too exhausting and Anne’s baby was stillborn. Assistant minister John Cotton smugly responded that God’s punishment was justly due.

But Anne was not to be stopped. She was fighting for the right of women to read for themselves, to think and come to their own understanding of God. And women lived in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, as well as Boston, Massachusetts.

Boston was not happy. They sent a letter to William promising to forgive him if he would but denounce his wife’s teaching.

“I am more nearly tied to my wife than to the church,” he wrote back, declining. “And I look upon her as a dear saint and servant of God.”19

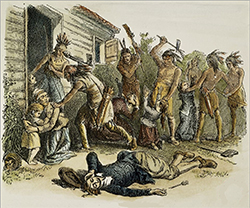

In 1642 William died, leaving Anne without support in a time when Boston was moving to gain jurisdiction over Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Having accused her of heresy, they now accused her of witchcraft. Having no other recourse she moved into a Dutch territory on Long Island, only to find the Dutch and Indians at war. A year after William died she was killed, along with five of her six children still living at home. The Bostonian clergy and government rejoiced. “God’s hand is apparently seen herein,” said Governor John Winthrop. “Proud Jezebel has at last been cast down.”20

Anne Hutchinson fought gallantly for the right of women to seek their own personal experience with God, and for that fight she died. It appears religious intolerance won the day.

Or did it?

Years ago I visited Boston, a city rich with a history of bloodshed and contradiction. A larger-than-life statue of Anne sits on the front lawn of the government building. I had not expected to find her there, and for a long time I sat amidst the roses planted nearby, watching the sun glance off the determined and noble bronze jaw of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Had she died in vain? Yet here she was. Her death a monument to religious freedom, once denied, now bedrock to American society.

Years ago I visited Boston, a city rich with a history of bloodshed and contradiction. A larger-than-life statue of Anne sits on the front lawn of the government building. I had not expected to find her there, and for a long time I sat amidst the roses planted nearby, watching the sun glance off the determined and noble bronze jaw of Anne Marbury Hutchinson. Had she died in vain? Yet here she was. Her death a monument to religious freedom, once denied, now bedrock to American society.

Footnotes:

15. Gail Reifert and Eugene M. Dermody, Women Who Fought: An American History (Reifert and Dermody, 1978), 8.

16. Reifert and Dermody, Women Who Fought, 8.

17. Lyle Koehler, “The Case of the American Jezebels: Anne Hutchison and Female Agitation during the Years of Antinomian Turmoil, 1636-1640,” in Linda K Kerber and Jane DeHart-Mathews, eds., Women’s America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 59.

18. Koehler in Kerber and DeHart-Mathews, eds., Women’s America, 59.

19. Reifert and Dermody, Women Who Fought, 9.

20. Reifert and Dermody, Women Who Fought, 9.