Sackcloth and Ashes

by Brenda Wilbee, in Memoir

, Christianity

, Reflection

, History - Family

MY FAMILY moved to Meteor Ranch of Northern California in May of 1962. Back then, my sisters and I were eight, nine, and ten, me in the middle, Linda and I were about to turn ten and eleven.

The ranch was a family-run Christian Conference Center and Bible Camp, the mother in charge. She oversaw her husband, sons, and daughters-in-law, the staff, and whatever wards of the state she could take in for cash flow—to use and misuse we’d learn soon enough. I’d already pegged her for a sheep in wool’s clothes. After hiring Dad to come work for her at a pittance by bribing him with a “fully furnished house,” we discovered the house to be a stolen ranger station she’d had her sons saw in half and haul out of the hills.

But this, our first full day, Mum volunteered Linda, Tresa, and I to set tables in the staff dining room tucked behind the kitchen, visible through a pass-through window above the kitchen sinks.

The kitchen itself was a big cube with pink wainscoting, high dirty-white walls, pale-yellow cupboards that sixty years later stood condemned by the State. But back then, two giant tables took up the center. The cooks, Ken and Ila Mae, a young couple and pregnant, showed us where the cutlery was stowed in gray totes atop a counter, and, in the cupboards above, cups, mugs, and plates galore.

“Grab a tote each,” said Ila Mae. “Follow me.”

I helped myself to the knife bin and trailed her and my sisters into the mud room (windows filigreed in cobwebs), a sharp left, and there we were. A bright room. Stifling hot. Six tables, a tangle of metal chairs, and California’s beastly sun pouring in through two windows like thick golden syrup and sticky.

“We’ll need twenty places tonight,” said Ila Mae, disappearing, her head reappearing through the pass-through window. We gratefully dropped our heavy totes on the end of one table, not sure where to start—or even what to do.

“Let’s begin with the plates,” said Linda, the oldest, “then the silverware. Five settings to four tables.”

Melmac, the plates. Easy to carry and we were just setting them out when a boy appeared.

I jumped, dropped a plate, and jumped again at the bouncing clatter.

He laughed and skirted a table to pick up my plate. Blond crewcut, blue eyes, fine features. If I had to guess, eleven? He gave it a blow.

“Good enough,” he said and handed it to me.

“But you just blew your germs all over it!”

“Not like I’m dying. Ken said to help you guys.”

“Who are you?” Linda asked.

“Richie. Aren’t you hot?” He navigated the tables to a double-hung window at the back and tugged up. A breeze riffled in. “What’re your names?”

“Linda. That’s Tresa over there.”

Tresa, taking a cue from Richie, was tugging up a side window, more air slipping in.

“And you?” he asked, slipping a book under the window to keep it open and turning to face me. “What’s your name?

"Don't tell him, Brenda!" she hollered.

It took a sec—for all of us.

Richie broke first. “Don’t tell him, Brenda!” he shrieked. Linda and I echoed. Tresa whirled, window behind her coming down with a crash and a bang, and then we were all laughing, staggering around the hot, stuffy room with a single lovely breeze teasing in. We couldn’t catch our breath.

“Don’t tell him, Brenda!” Richie wheezed.

"Don't tell him, Brenda!" I wheezed.

“I’m so stupid!” snorted Tresa in tear-wiping giggles. None of us could stand. We grabbed metal chairs, tripped over the legs, grabbed another chair, don't tell him, Brenda! flying off the walls like bees at our ears and we whelped and mewed and snorted through our noses. We’d just draw breath and think we were over it—but off we’d go again. Until the woman in charge came in. We sobered up in a hurry, but the minute she left we were at it again, our stifled guffaws laced with laughter as we staggered in circles around the tables, setting out the cutlery. Forks left of the plates. Knives to the right, blade pointing in. Spoons. Queen Elizabeth couldn’t have been prouder.

“Sixty pieces!” I crowed, multiplying the silverware, math in my head with no place else to go but out.

Richie, it turned out, had been turned over to the State by his mother. The woman in charge got $400 a month for him and the State and his mother were both unaware that he’d been given a hard row to hoe. Mum and Dad spoke of adopting him, but when the darkness of Meteor Ranch proved too much for us all, Richie’s mother put a kibosh on letting him go out of state. Eight months after arriving, we left, leaving not only Richie but others. Uncle Earl, Jack, Joe, Ben…

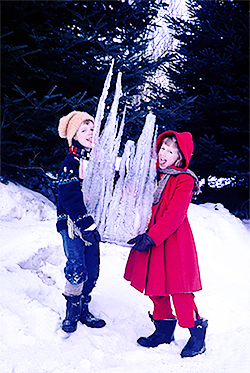

We wound up in the Laurentian Mountains of French Canada, an idyllic oasis without shadow. But here I began to tear out my hair, my guilt having no other way to express.

We wound up in the Laurentian Mountains of French Canada, an idyllic oasis without shadow. But here I began to tear out my hair, my guilt having no other way to express.

Woe is the culture that creates abuse without offering sackcloth and ashes.

I hope Richie's found a way to live with the lonely, unspoken trauma of his childhood.

The kitchen itself was a big cube with pink wainscoting, high dirty-white walls, pale-yellow cupboards that sixty years later stood condemned by the State. But back then, two giant tables took up the center. The cooks, Ken and Ila Mae, a young couple and pregnant, showed us where the cutlery was stowed in gray totes atop a counter, and, in the cupboards above, cups, mugs, and plates galore.

“Grab a tote each,” said Ila Mae. “Follow me.”

I helped myself to the knife bin and trailed her and my sisters into the mud room (windows filigreed in cobwebs), a sharp left, and there we were. A bright room. Stifling hot. Six tables, a tangle of metal chairs, and California’s beastly sun pouring in through two windows like thick golden syrup and sticky.

“We’ll need twenty places tonight,” said Ila Mae, disappearing, her head reappearing through the pass-through window. We gratefully dropped our heavy totes on the end of one table, not sure where to start—or even what to do.

“Let’s begin with the plates,” said Linda, the oldest, “then the silverware. Five settings to four tables.”

Melmac, the plates. Easy to carry and we were just setting them out when a boy appeared.

I jumped, dropped a plate, and jumped again at the bouncing clatter.

He laughed and skirted a table to pick up my plate. Blond crewcut, blue eyes, fine features. If I had to guess, eleven? He gave it a blow.

“Good enough,” he said and handed it to me.

“But you just blew your germs all over it!”

“Not like I’m dying. Ken said to help you guys.”

“Who are you?” Linda asked.

“Richie. Aren’t you hot?” He navigated the tables to a double-hung window at the back and tugged up. A breeze riffled in. “What’re your names?”

“Linda. That’s Tresa over there.”

Tresa, taking a cue from Richie, was tugging up a side window, more air slipping in.

“And you?” he asked, slipping a book under the window to keep it open and turning to face me. “What’s your name?

"Don't tell him, Brenda!" she hollered.

It took a sec—for all of us.

Richie broke first. “Don’t tell him, Brenda!” he shrieked. Linda and I echoed. Tresa whirled, window behind her coming down with a crash and a bang, and then we were all laughing, staggering around the hot, stuffy room with a single lovely breeze teasing in. We couldn’t catch our breath.

“Don’t tell him, Brenda!” Richie wheezed.

"Don't tell him, Brenda!" I wheezed.

“I’m so stupid!” snorted Tresa in tear-wiping giggles. None of us could stand. We grabbed metal chairs, tripped over the legs, grabbed another chair, don't tell him, Brenda! flying off the walls like bees at our ears and we whelped and mewed and snorted through our noses. We’d just draw breath and think we were over it—but off we’d go again. Until the woman in charge came in. We sobered up in a hurry, but the minute she left we were at it again, our stifled guffaws laced with laughter as we staggered in circles around the tables, setting out the cutlery. Forks left of the plates. Knives to the right, blade pointing in. Spoons. Queen Elizabeth couldn’t have been prouder.

“Sixty pieces!” I crowed, multiplying the silverware, math in my head with no place else to go but out.

Richie, it turned out, had been turned over to the State by his mother. The woman in charge got $400 a month for him and the State and his mother were both unaware that he’d been given a hard row to hoe. Mum and Dad spoke of adopting him, but when the darkness of Meteor Ranch proved too much for us all, Richie’s mother put a kibosh on letting him go out of state. Eight months after arriving, we left, leaving not only Richie but others. Uncle Earl, Jack, Joe, Ben…

We wound up in the Laurentian Mountains of French Canada, an idyllic oasis without shadow. But here I began to tear out my hair, my guilt having no other way to express.

We wound up in the Laurentian Mountains of French Canada, an idyllic oasis without shadow. But here I began to tear out my hair, my guilt having no other way to express.Woe is the culture that creates abuse without offering sackcloth and ashes.

I hope Richie's found a way to live with the lonely, unspoken trauma of his childhood.