The Lone Woman of San Nicholas

.jpg)

A WOMAN KNOWN ONLY as the Lone Woman has a story we cannot know. Yet we try.

She was born on San Nicholas Island off the coast of Santa Barbara’s Channel Islands in the early 1800s, a small outcropping of sandstone and sea mist, home to the Nicoleño for millennia. She was but a child in 1811 when Alaskan Kodiak Indians of the Russian Fur Trading Company arrived to hunt sea otters. One of them killed a Nicoleño man. Oral tradition so old it disintegrates on contemplation leaves however an impression of a quarrel over a woman. Whatever the reason, it ended in a bloodbath, every male on the island slaughtered and women who had no place to run raped. The population, cut in half, plunged. Gradually the Channel Indians abandoned their homes for the mainland--often encouraged not so subtly by the Spanish Catholic Church.

In 1835, the Church heard that a handful of Nicoleño still lived on San Nicholas, the most remote of the Channel Islands, and they sent Captain Hubbard on his “Peor es Nada” (“Better Than Nothing”) to round them up. By force, bribery, cajoling, who knows. But all were brought down to the beach and rowed out to the ship in skiffs. Except two. Two versions of what happened arise from the fog of time. A woman had either gone looking for her son or she’d dived off the ship when she learned he was missing. Either way, a sudden storm blew in and Capt. Hubbard, hedging his bets, decided it was better to risk the high winds and turbulent water in a hasty retreat back to Santa Barbara than flounder on the craggy shoreline of San Nicolas. The Church sent several expeditions after her, paying as much as $200 for an attempt. But when no trace of her or a child could be found, she was given up for dead and fell into legend. Until 1853, eighteen years later.

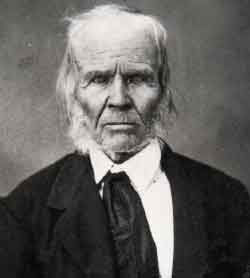

The year before, in the fall of 1852, Capt. George Nidever, with a small crew of sea otter hunters, put in and discovered a woman’s footprints in the sand. Finding no sign of life, they continued to hunt around the islands, trapping and skinning otters and looking for seagull eggs, a delicacy. Back home in Santa Barbara for the winter, the friars at the mission encouraged him to return and make a more serious attempt to find her.

In May, he set out again. Nothing. And then again in late July with his friend Charley Brown, plus a man they called Colorado and four mission Indians—three hunters and a cook. They put in at the place where he’d seen the footprints the fall before a sandy beach awash with seaweed and seashells—abalone, blue muscle, limpets, razor clams. Hummingbirds darted about. Overhead, bald eagles and wrens, cormorant, the snowy plover and meadowlark, the wheeling osprey, all fluttered and banked, warbling and shrieking according to kind, a chorus to the musical lap of the waves. Ducks flew in and waddled about. Fox and wild dogs (with a flare of Alaskan husky) yipped and barked. Field mice and alligator lizards scuttled the seagrass. Seals sunned on the rocks. The sea otter innocently played.

The men hauled ashore their equipment for trapping and skinning the otter, and for drying the pelts. Late in the day, they spotted prints. Romanticized versions of what followed pale in comparison to what Capt. George Nidever dictated twenty-five years later. His specifics lend authenticity other tales lack.

The condensed version is that in the morning they found an “old woman” in a rude hut made of whale ribs patched with seagrass and brush. She wore a dress of cormorant skins, feathers out and sewn together with seal sinew, her long hair matted, sun-bleached to reddish brown. She sat cross-legged, peeling blubber off a seal hide draped over a knee with a crude knife. And although she saw them approach, she kept at her work. When surrounded, and when Charley Brown stepped out in front of her, she looked up and smiled.

The men were astonished at her welcome—and ingenuity. Nearby, she’d skewered blubber atop stakes to dry in the sun and had slabs of it hung over sinew ropes. Scattered about were baskets in varied stages of completion, woven together from various grasses to create designs. Two bottle-shaped flagons had been water-proofed with melted asphaltum, a black pitch. Fishhooks made of bone. Bone needles. More sinew rope and fishing lines. She showed them a cave she used as a shelter from storms.

They, in turn, introduced her to the ship, gave her a berth that night (and every night) and shared their food (which she devoured, favoring anything sweet). Charley made her dress of bed ticking and a man’s shirt and necktie. Nidever gave her an old cape. She pantomimed that she wanted a needle and thread—though they had to help her thread it, her eyes apparently going bad. She spent days mending the rips and wore it with pride. On shore, she worked on one basket after another, never finishing them, just trading them . For hours, she batted a doll made from a baby seal that she’d strung from the ribs of her whale bone hut. Bored with that, she helped them snare the otters and skin the fur. She fetched water, fetched firewood. Readily she agreed to go with them to Santa Barbara when they left.

She died seven weeks later.

Santa Barbara, more of a town than a mission in 1853, entertained and delighted her. While being rowed ashore, she marveled at this new world, drawing everyone into her excitement. While putting in, she spotted an oxcart and, familiar only with wild dogs and having never seen a wheel, she shrieked with glee. And when one of Capt. Nidever’s sons rode up on a horse, she scrambled out of the skiff to slide her hands in wonder over the animal. She laughed and used two fingers from her right hand to straddle a finger on her left, wiggling them to indicate riding. Her ready smile—teeth worn to the gum—endeared her to everyone who gathered. She went home with the sea captain, to his Spanish wife and 14,000-acre farm.

Her seven weeks were a happy time. She relished the fruit, anything with sugar, liquor of all kinds. She loved going into town, almost always coming home with gifts. People were taken by this legend come true, and her unconventionality intrigued them. She did as she pleased—singing, dancing, poking her nose into whatever caught her curiosity.

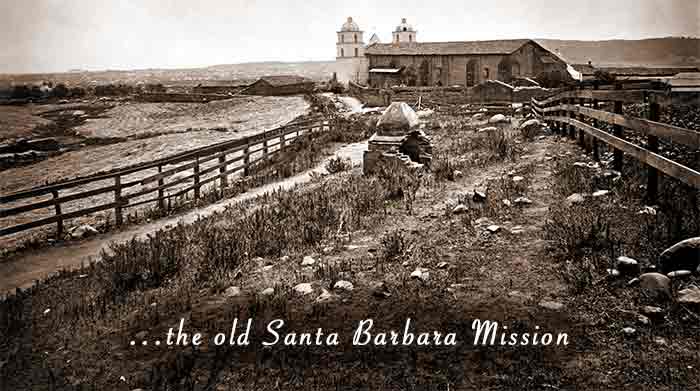

Visitors came out to the ranch to sit with her on Niveder's veranda in shadow of the Mission, overlooking the sea. Eagerly she showed them her things and eagerly they examined artifacts of a simpler civilization. And despite the language barrier, she managed to relay information through sign language and pantomime. According to Nidever, she never did find her son and concluded that wild dogs had eaten him. Charley Brown read it differently. He thought she told of a teenage son who died while out fishing, his canoe tipping over and being devoured by sharks. Sign language and pantomime left a lot open to interpretation.

Visitors came out to the ranch to sit with her on Niveder's veranda in shadow of the Mission, overlooking the sea. Eagerly she showed them her things and eagerly they examined artifacts of a simpler civilization. And despite the language barrier, she managed to relay information through sign language and pantomime. According to Nidever, she never did find her son and concluded that wild dogs had eaten him. Charley Brown read it differently. He thought she told of a teenage son who died while out fishing, his canoe tipping over and being devoured by sharks. Sign language and pantomime left a lot open to interpretation.Eager to know her story—and probably to convert her, this being church policy for all aboriginals in Spanish America—Father Gonzales sent for Indians from Los Angeles, where the last of the Nicoleño had been sent in 1835. But all had perished. A few from elsewhere, however, recognized four words; and one memorized a song she frequently sang. Years later he recorded it, and linguistics ever since have studied the lyrics but can't link it to anything known. Left so long on her own, it seems the Lone Woman’s native tongue had devolved into something only useful to her.

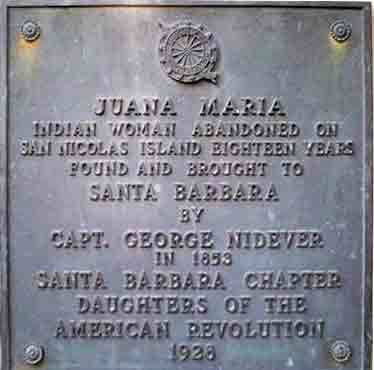

She died seven weeks to the day of her arrival—of dysentery, the same disease that killed Channel Island Indians by the thousands after coming to the coast. The white man’s diet wreaked havoc on stomachs only used to raw fish, duck, blubber, bird eggs, and seal oil. Conditionally baptized by Father Gonzales, who gave her the name Juana Maria on her death bed, she is buried in the Santa Barbara Mission cemetery, her life and death commem-orated in 1928 by the Daughters of the American Revolution. And so the Lone Woman fades back into legend, her real story anyone’s guess.

She died seven weeks to the day of her arrival—of dysentery, the same disease that killed Channel Island Indians by the thousands after coming to the coast. The white man’s diet wreaked havoc on stomachs only used to raw fish, duck, blubber, bird eggs, and seal oil. Conditionally baptized by Father Gonzales, who gave her the name Juana Maria on her death bed, she is buried in the Santa Barbara Mission cemetery, her life and death commem-orated in 1928 by the Daughters of the American Revolution. And so the Lone Woman fades back into legend, her real story anyone’s guess.

People continue to guess. Experts from the Smithsonian, the National Park Service, new archeological digs, all bring information to the story while simultaneously making it more mysterious and more contradictory than ever. The most famous “guess” is Scott O’Dell’s. His 1960 historical novel, Island of the Blue Dolphins, won a Newbery Award and justly so. Only in fiction can we really get at the truth. In this case, the essence of a woman known only as Lone Woman. His Karana is the closest we’ll get to learning the heart and courage of a woman who is perhaps not dead after all, but who lives in the imagination of us all.