Seattle Meets Captain George Vancouver

LONG BEFORE LOUISA WAS BORN, six-year-old Seattle on the west coast of the continent felt his privilege at even so young an age. Son of Suquamish Chief Schweabe and grandson of a Duwamish chief, slaves did his bidding. He never had to paddle his canoe; his legs were therefore straight, not bowed. When food was scarce, he ate. People greeted him with warmth. Sometimes he joined his father and uncle, the war chief, when they traveled north to confer with the Lummi, or south to speak with the Nisqually. At times his band paddled across the Wulge (Salt Water) to visit his mother’s people where they lived in scattered villages up the Duwamish River and along the east side of the inland sea. Home, however, was Old Man House on an island channel to the west; and here in a massive, six-hundred-foot apartment complex, tucked under the cedar trees along a beach where agates tumbled in on the tide, the little boy lived secure in his world. He knew its seasons, its dangers, its safety and stories.

LONG BEFORE LOUISA WAS BORN, six-year-old Seattle on the west coast of the continent felt his privilege at even so young an age. Son of Suquamish Chief Schweabe and grandson of a Duwamish chief, slaves did his bidding. He never had to paddle his canoe; his legs were therefore straight, not bowed. When food was scarce, he ate. People greeted him with warmth. Sometimes he joined his father and uncle, the war chief, when they traveled north to confer with the Lummi, or south to speak with the Nisqually. At times his band paddled across the Wulge (Salt Water) to visit his mother’s people where they lived in scattered villages up the Duwamish River and along the east side of the inland sea. Home, however, was Old Man House on an island channel to the west; and here in a massive, six-hundred-foot apartment complex, tucked under the cedar trees along a beach where agates tumbled in on the tide, the little boy lived secure in his world. He knew its seasons, its dangers, its safety and stories.His favorite was “The Flood.” Days and days and weeks of rain, unrelenting until all that was left was the sea. But someone had thought to save the animals by lashing together canoes and putting two of every kind on board. When at last the floodwaters receded and the dugouts came to rest on Mt. Sumas, the animals were able to disembark and repopulate the earth. There were other stories, many. But this was a favorite. Who was the man who knew how to save the animals? Did he have a name?

.jpg)

In the spring of 1792, six-year-old Seattle and his village paddled south to their annual camas dig. Moon of Digging Up: Time to harvest the bulbs of tall purple flowers growing in estuary meadows. The women cobbled together shanties by using last year’s abandoned cedar planks, mindful to set the shelters behind the seaweed ribbons and driftwood, away from high tide. Some of the lean-to’s they draped in woven cedar blankets to stay the rain. Fire pits had to be re-dug, wood had to be gathered so they could first cook, then preserve, the protein-rich food. One morning, mid-month, the early morning fog hung low. The women were already in the meadow, using antler spades to dig up the flowers and tossing the blue bulbs into cedar baskets strapped to their backs. The men lay in hammocks while slaves sat on driftwood close to shore, sharpening arrowheads and mending fish nets.

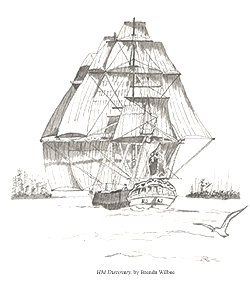

Chilled by the mist, Seattle shivered. Barefoot and naked (although well greased in fish oil), he and four other boys squatted on their haunches. It was Seattle’s turn to guess in which hand Klacum held the small bone. A startled scream brought him to his feet in a panic. But it wasn’t the Haida, northern invaders who descended in swift surprise and brutal attack. Worse. Seattle gaped in frozen fear as an enormous canoe emerged from the fog, humongous and out of this world. High white wings hung from three trees that grew straight up from the dugout floor. Mothers came screaming in great leaps to seize their children, and he flinched at the icy dagger of fear that knifed from his mother to him. Quickly he pulled loose. Where was his father? He spun a thousand directions. The beach! He arrived just as Chief Schweabe bellowed for silence.

Instant quiet settled over the crowd, except for the whimpering of small children and the gentle lap of waves washing on the shingle. Seattle took his father’s hand and watched in disbelief as pale-skinned creatures began folding the great white wings and dropping an enormous anchor into the sea.

“Who are they?”

“People of the Prophecy,” said his father. He’d not been told this story. His father and the war chief, the most powerful man on the Wulge, talked in hushed tones. They’d take the best warriors and surround the boat. The others would stay on the beach and prepare to defend. Next thing Seattle knew, he was scrambling into his uncle’s ornately painted war canoe, one of three to approach the mirage.

When they drew near, curved walls towered above him. Above, white faces peered curiously down. A rope ladder fell off the side, and Seattle scrambled up behind his father with jelly legs and shaking hands. On board, he stood blinking. A man—was he a man?—indicated they follow. They tripped over coiled rope and guy-wires and skirted stacked cages of squawking birds, the likes of which he’d never seen. Nor had he seen pink boars before, and wondered why they were kept in pens. A raucous bird of wild colors he didn’t know possible sat atop a man’s shoulder. Seattle followed him, and his father, down a steep, narrow stair leading into a darkened cavern. He stuck close, agog, curiosity and astonishment slowly replacing fear.

Who could imagine such things?

Chilled by the mist, Seattle shivered. Barefoot and naked (although well greased in fish oil), he and four other boys squatted on their haunches. It was Seattle’s turn to guess in which hand Klacum held the small bone. A startled scream brought him to his feet in a panic. But it wasn’t the Haida, northern invaders who descended in swift surprise and brutal attack. Worse. Seattle gaped in frozen fear as an enormous canoe emerged from the fog, humongous and out of this world. High white wings hung from three trees that grew straight up from the dugout floor. Mothers came screaming in great leaps to seize their children, and he flinched at the icy dagger of fear that knifed from his mother to him. Quickly he pulled loose. Where was his father? He spun a thousand directions. The beach! He arrived just as Chief Schweabe bellowed for silence.

Instant quiet settled over the crowd, except for the whimpering of small children and the gentle lap of waves washing on the shingle. Seattle took his father’s hand and watched in disbelief as pale-skinned creatures began folding the great white wings and dropping an enormous anchor into the sea.

“Who are they?”

“People of the Prophecy,” said his father. He’d not been told this story. His father and the war chief, the most powerful man on the Wulge, talked in hushed tones. They’d take the best warriors and surround the boat. The others would stay on the beach and prepare to defend. Next thing Seattle knew, he was scrambling into his uncle’s ornately painted war canoe, one of three to approach the mirage.

When they drew near, curved walls towered above him. Above, white faces peered curiously down. A rope ladder fell off the side, and Seattle scrambled up behind his father with jelly legs and shaking hands. On board, he stood blinking. A man—was he a man?—indicated they follow. They tripped over coiled rope and guy-wires and skirted stacked cages of squawking birds, the likes of which he’d never seen. Nor had he seen pink boars before, and wondered why they were kept in pens. A raucous bird of wild colors he didn’t know possible sat atop a man’s shoulder. Seattle followed him, and his father, down a steep, narrow stair leading into a darkened cavern. He stuck close, agog, curiosity and astonishment slowly replacing fear.

Who could imagine such things?

Flat stones with blue pictures—to eat from! Thin shiny baskets that tinged when tapped! A high soft bed! Fluffy covers! Images on the walls! Round holes that let in the light! He went up on his toes to see through, but snubbed his nose. What’s this? Something, but nothing? He tried sticking his hand through. He tried again. Behind him, a black box crackled and spit, and he shrieked in surprise when someone opened a small door and he saw a fire inside. Why didn’t the box burn up?

Flat stones with blue pictures—to eat from! Thin shiny baskets that tinged when tapped! A high soft bed! Fluffy covers! Images on the walls! Round holes that let in the light! He went up on his toes to see through, but snubbed his nose. What’s this? Something, but nothing? He tried sticking his hand through. He tried again. Behind him, a black box crackled and spit, and he shrieked in surprise when someone opened a small door and he saw a fire inside. Why didn’t the box burn up?Back on deck, someone gave him a stick to look through. Everything so big! How did his mother get in the stick? He gave it a shake. He waved. She didn’t wave back. Didn’t she see him? He turned the stick around and looked through the other end. A black hole.

Someone else gave him a small white cube to put in his mouth. He burst out laughing! “Sugar,” he repeated, and the man—or was he a god?—laughed too, and invited him to take another. He did, and laughed again.

The pale, god-like beings were the most curious of all, unintelligible in their speech but eager to show off. Their white skin both horrified and delighted him. One had glowing red hair, like a sunset on fire, a flowing beard of the same color. Many had blue eyes. Had these creatures come from the sky? Many wore elaborate, ornate jackets with bobbles and braiding; rows of shiny briny buttons; long, curved sheaths strapped to their waists. Others wore simple shirts, and when he touched one to see how it felt, the Being pulled it off and gave it to him. He didn’t know what to do, so the man, the god, they had to be gods, wiggled Seattle’s arms into it and laughed, and pointed to Seattle’s feet. He looked down. The shirt came to his toes.

A god dribbled black powder into a stick and aimed at a seagull. BOOM! The bird exploded and Seattle, ears ringing, wondered what it would do to a man. Fear returned.

He spent the rest of the day trying to explain to his friends the many things he’d seen; but when in the morning the mysterious canoe left, wings fluffing before the wind, Seattle watched them go with an unsettled mind. That night under cover of darkness he buried the blue shirt in the meadow, frightened that it might somehow turn his skin white.

If you'd like to get on a mailing list to receive news of when the new Sweetbriar is released, please email me at Brenda@BrendaWilbee.com.