Love and Succor In Civil War - and Beyond

LUCY HIGGS WAS BORN A SLAVE in Gray's Creek, TN, the spring of 1838—property of Rueben Higgs and his wife Elizabeth. Seven years later they died. All their slaves went to the children; and Lucy, pulled from her mother's arms at only seven years old, went to Mississippi to the Higgs’s daughter, Wineford. When Wineford died in 1861, Lucy was 23. But back to Tennessee for her, again divvied out.

LUCY HIGGS WAS BORN A SLAVE in Gray's Creek, TN, the spring of 1838—property of Rueben Higgs and his wife Elizabeth. Seven years later they died. All their slaves went to the children; and Lucy, pulled from her mother's arms at only seven years old, went to Mississippi to the Higgs’s daughter, Wineford. When Wineford died in 1861, Lucy was 23. But back to Tennessee for her, again divvied out.

June 1962, rumor had the Union Army not far away. Lucy, her husband, her daughter Mona, along with a handful of others struck out, crossing the Hatchie River on a moonless night. From the audio portion of a display called "Remembered: The Life of Lucy Higgs Nichols" in New Albany's IN's Carnegie Center, we learn of their escape:

"Moon went out the night we ran away, but all I kept thinking was they gonna find us and we gonna be in for a beating. Maybe they’d kill us. Or maybe send me or Calvin away. Or maybe take my baby. By the time we got to the Union camp I couldn’t hardly breathe, I was so scared. And tears was running down my face. Sure enough, wasn’t two days later when Massah showed up at camp.

"'They’s my property here. Give em back now.'

"That didn’t sit so well with the Union men."

No one knows what happened to Lucy's husband, and sadly the little girl died during the Siege of Vicksburg, details missing. Lucy, too, would have gone in the wind but for a discovery by local historians in New Albany, IN, that document her slavery, escape, and subsequent life. What emerges is a story of love and succor in the civil war and beyond.

Major Shadrack Hooper of Indiana's 23rd spotted in Lucy a good and gentle nurse and put her work. Not just the Major approved. Every soldier adored her, and counted on her to see them through 28 battles and sieges.

Major Shadrack Hooper of Indiana's 23rd spotted in Lucy a good and gentle nurse and put her work. Not just the Major approved. Every soldier adored her, and counted on her to see them through 28 battles and sieges.

War over, she followed them back to New Albany, Indiana. Partly because she had no place go but mostly because they couldn’t imagine letting her go. There she nursed the returning wounded back to health and made a living for herself as a live-in domestic for the men and their families.

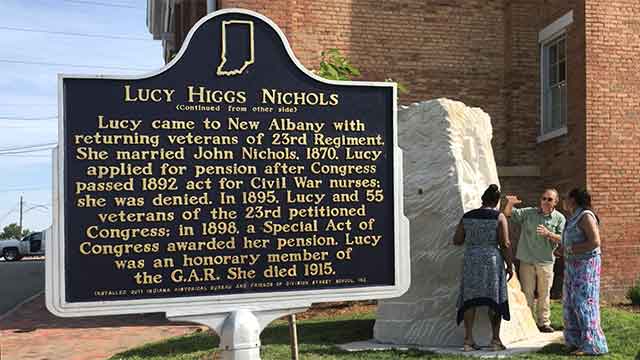

In 1866, civil war veterans created a fraternity called the Grand Army of the Republic. They made Lucy an honorary member. She attended every meeting and when denied a military pension (as so many nurses of color have been), the GAR took up her defense. A long fight. Not until she was 60 years old in 1898 did they secure for her a grant of $12 a month—making her a much publicized headline all over the country.

In the meantime, at 32 years old, she’d married John Nichols, a free-born musician; and for the first time in her life she had a home to call her own. When he died, she was left to scrape by as had always been her lot.

Though not forgotten.

When she came down with measles, the Boys of the 23rd nursed her back to health. When she had a stroke, they came to her aid. And when she died at 77 years old on January 25, 1915, a cold barren day with a wind blowing hard out of the north, a handful of the old loyal veterans saw her buried with flowers and tears.

Today Lucy lies undisturbed in an unmarked grave in New Albany's West Haven Cemetery, yet outside their Carnegie Center for Art and History stands a statue and historical plaque to honor her life, a story of love and succor in war—and beyond.