Memoir #2: Reflection vs Documentation

TO WRITE ABOUT OUR "UNRULY PAST" (as Laura Kalpakian names her own delicious memoir!) is by necessity a distortion of "fact" in order to name "truth." Away back when, we didn't have the words needed to name our experience. It's only time, education, and perspective that gives us the articulation we now need to make sense of what was. A memoirist therefore revisits her past with tools to reflect truth rather than document it. Except we run into a few dilemmas.

A first is . . .

.

.jpg) A close cousin are events that "didn't" happen. I was twelve when my mother took me to see the doctor for bronchitis. He stood behind me, feeling my glands, and got into an animated conversation with my mother, all the while squeezing harder and harder on my throat. I started to pass out and tipped forward and to the left off the examining table, everything going from gray to instant black.

A close cousin are events that "didn't" happen. I was twelve when my mother took me to see the doctor for bronchitis. He stood behind me, feeling my glands, and got into an animated conversation with my mother, all the while squeezing harder and harder on my throat. I started to pass out and tipped forward and to the left off the examining table, everything going from gray to instant black.I did ask Mum on the way home why he'd done it. "Why did he choke me?"

"He didn't choke you!"

Did he? Didn't he?

The next morning I had four bruises on each side of my larynx, eight total, ugly bruises lining my throat like buttons. On the back of my neck were two larger ones, where the doctor's thumbs had been. My mother argued the evidence. "Don't be silly, he didn't choke you." This kind of gas-lighting plays havoc on memory. What is the memoirist to do?

Dr. Phil says our perception is our reality. A memoirist writes the truth of her experience.

A more difficult dilemma is dealing with deep "in-the-breastbone" emotion that existed without action. There is nothing for a reader to see, therefore nothing to relate to. Who cares what I feel, or what I think? I'm a dime a dozen. But if I give a narrative picture? And invite readers into my time and place? Maybe they will find themselves in the same time and place.

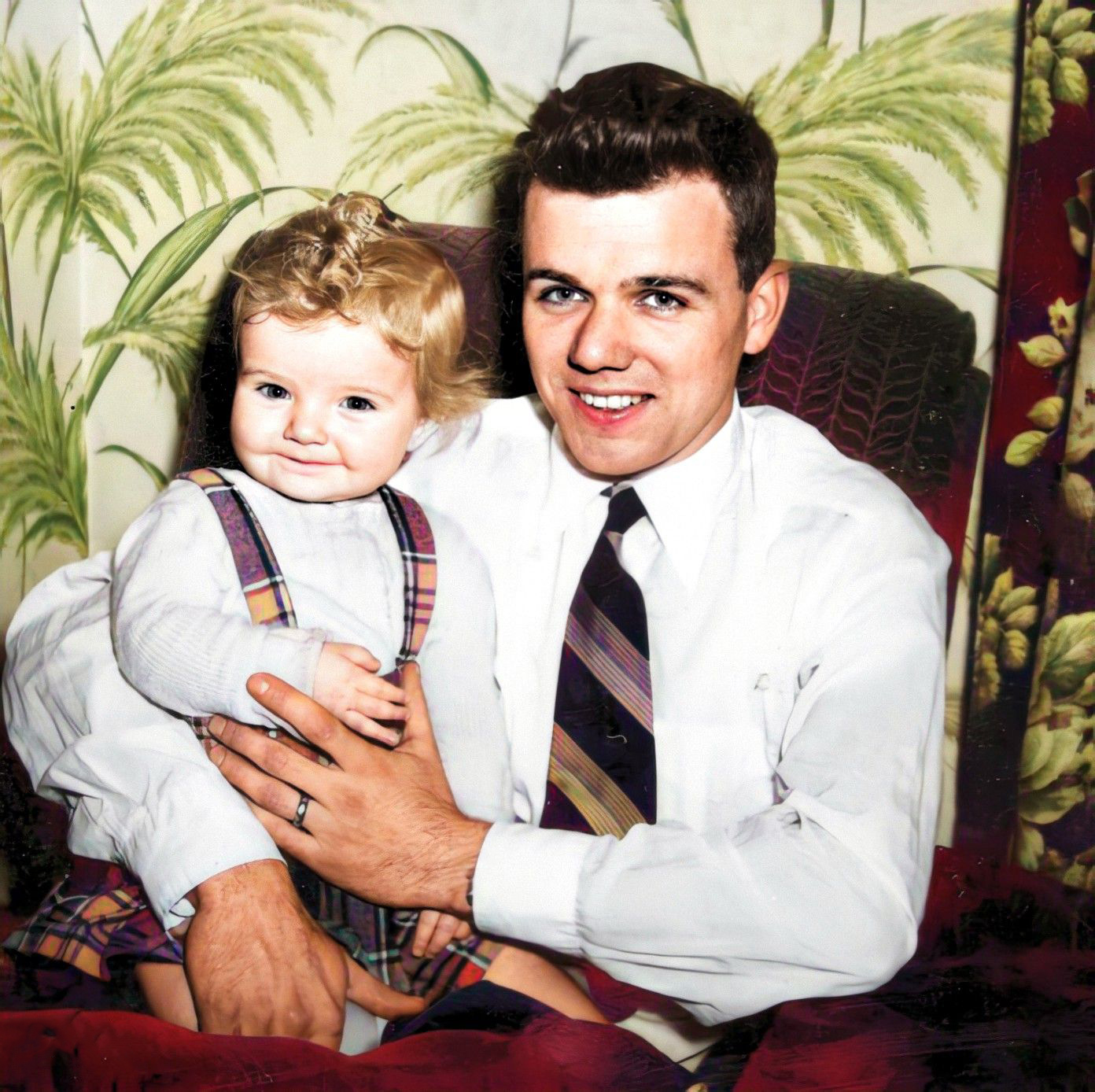

I was stuck on Chapter Four forever, trying to communicate how my little sister's short life and death impacted me. Blah blah blah wasn't working. I finally ended up with this. I am nine. Heather had died the week before at just three and a half years old.

God’s smile, hung from the stars, fell. And I didn’t know where to find the shattered pieces.

At home, Mum and Dad’s friends milled under Dad’s cathedral ceiling made from our trees, the smell of Two Penny tea and minced-meat tarts and Grandma’s matrimonial bar infusing the air. I threaded the crowd, weaving conversations. And then there it was."At least the girls don’t have to live in death’s shadow anymore. Such a terrible thing, all these years knowing such a day would come."

They didn’t understand. Knowing gave me everything. Her finger on the pussy willow. Recognition in her eyes. A weary smile. Her song at dawn and in the dusk. Pink may-he-dun first, then blue. Shiny black shoes when no one thought she’d walk. Truth—a necessary knowing. A cornerstone.I slipped down the hall to her crib and climbed in. I had everything. And in this everything, I found God’s shattered smile.

Perhaps my readers relate and recollect—in their own "unruly lives"—God's shattered smile.

These are but three dilemmas for the memoirist: Misaligned memories, uncertain memories, and memories layered and that only later can be articulated. There are more, of course. Like what to talk about about and what not to say. Every good photographer has to throw out a thousand images to retain the singular perfect one. Every memoirist has to throw out decades of memories to retain only those that shape and inform and make meaning. I'll write about that next week.

I conclude with Kalpakian's definition of a memoir, as written in her new book, Memory Into Memoir, published by the University of Mexico Press.

Writing a memoir mean revisiting, reviving family stories.

Writing a memoir can be an act of courage or gratitude or a plea for understanding, even a bulwark against loss.

Writing a memoir means reconsidering what you thought you already knew.

Writing a memoir does not created the past, or even re-create the past, but makes it legible.