Memoir #1: On Making Stuff Up

by Brenda Wilbee, in Memoir

"Your writing strength is scene, Brenda," so says Laura Kalpakian, a mentor of sorts. "Play to your strengths. You've zipped right through this narrative. I can't see any of it. What does the courtroom look like? Who's there? What is being said?"

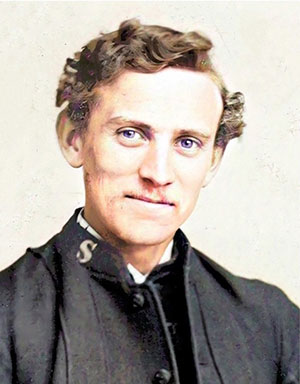

The thing is, I didn't want to overly dwell on my great-great-grandfather and his day in court. I only wanted to establish the faith of my grandfathers as a long-standing heritage that both helped and hindered me. Besides, Sarratt, England, doesn't and didn't have a court house. It's just a hole-in-the-wall 30 miles NW of London and I'm really not sure where the hearing took place. More to the point, do I really want to make a scene of it?

I've learned over the years to concede to Laura. Though I did push back...a little.

"I don't know enough to create the full scene," I tell her.

"Then make it up!"

Geez, no problem. If it was fiction.

I stew around a bit and then it comes to me. Admit I'm making it up!

So this is what I did. I started the scene with a narrative of George William Wilbee (1841-1921):

What irked my Baptist great-great-grandfather—grocer, baker, butcher, draper, and upholsterer in Sarratt, England, a scant thirty miles northwest of London—was having to pay taxes to support the national public schools run by the Anglican Church, a marriage of Church and Crown he just had to kick. He first sent his eldest, Lillian, to a boarding school lest the theology of transubstantiation mess with her head; but when it came time to send nine-year-old Arthur, the boy was too sickly. I suspect bronchitis. In March of 1878, then, George was summoned to answer a charge of truancy on behalf of his son. If Arthur wasn’t enrolled in boarding school, he had to attend the local school, Anglican though it was. George was thirty-seven, and here I have to let my imagination run a bit loose—

I boldly announce I'm about to make stuff up.

...and here I have to let my imagination run a bit loose—tethered however to a yellowed news column—to fully picture this.

Even though I'm about to make this next bit up I want my reader to know it is based on documentation.

He and his lovely wife Martha sit side by side on a bench in the rather plain courtroom of Sarratt House. There is the Union Jack and requisite picture of King George V. Martha nervously folds her hands, maybe fusses with a hat pin, maybe chews her lip. George fumbles his paperwork. Arthur, definitely frail, certainly shy, sits between them, blonde curls untamed and head tucked to one side so he can surreptitiously, in his mind at least, suck on his shirt collar, a characteristic he passed down to his grandson (my father), my father to me. Martha doesn’t bother to lift his chin.

“Is there a reason you deny your son his three R’s?” questions the imposing figure of the wigged magistrate, looking down his Grecian nose at the family. “Do you think reading, writing, and arithmetic not worthy pursuits? Is your boy to remain an uneducated Pooh?”

The scene is launched and goes for three pages. Laura's right. My reader is going to forever thank me for this one line alone—"Is your boy to remain an uneducated Pooh?"

No bah blah blah here.

As it turns out, Arthur outgrew his childhood bronchitis and crippling shyness.

I then narrate a couple of hurried "Little Grandpa" stories (named Little Grandpa by his grandchildren because of his height—five foot two). Vancouver's city police would have locked him up and fed him yesterday's bread had he not been so rich. Rich, he was simply deemed "eccentric." I then tell a story of how Little Grandpa got annoyed with his grown children for choosing the higher profit margins of manufactured brooms over those made by the blind. Capitalism gone awry. Justice cut short. He put posters in the WILBEE SERVICE STORE windows and painted footsteps leading to the competition. I switch to present tense to alert the reader I am about to make this next bit up.

In the morning, my grandfather Victor tidies his tie, sips the last of his Two Penny tea, and takes my grandmother’s garden trail out to Fraser Street, letting himself onto the sidewalk just two storefronts from WILBEE’S SERVICE STORE #3. Footprints. He doesn't need to read his father’s sign in the window to know what's going on. There it is: “Buy brooms from the blind. Sold everywhere but here.” The police are on the phone before Grandpa can even let himself in. I can almost hear the conversation.

"I can almost hear" serves to remind the reader that I'm in scene. I'm making this up.

“Victor, Dombrowski here.…" A sympathetic voice on the other side of the phone call. "Get those footprints painted over, or we’ll have to arrest him for defacing public property.”

Creating a scene from my own life poses a slightly different challenge. It's not a matter of not knowing what was said but not remembering the exact words—and you know someone with a better memory is going to call you on it. Still, my memory is important. I'm writing a memoir after all. In Chapter 1—I Am Engaged—I create the gist of a "never-ever-to-be-forgotten" converstation by admitting up front I'm about to fudge.

I can’t recall the precise conversation, and I’m embarrassed to paraphrase. It reveals an astonishing lack of critical thinking and self-preservation.

“Love the Lord with all your heart,” he reads.

“Love your neighbor as yourself,” he quotes.

“You’re required to love me,” he reiterates.

“You must be lay down your life for me,” he says.

Admit and switch.

1) "...let my imagination run a bit loose...,"

2) "I can almost hear...,"

3) "I don't recall / am embarrassed to paraphrase..."

"Your writing strength is scene, Brenda," so says Laura.

Well…it helps to have a foot-loose and fancy-free imagination. But this begs the question: Why is scene better than the narrative blah-blah-blah? And for writers who lack my run-with-it imagination? Should they write in scene? This is what I have to say about that:

It's like going to the movie theatre to see Kevin Costner. The music starts, the lights go dim, he's about to have his foot sawn off on a Civil War battlefield somewhere. You're really into this, what will happen? You see what he sees: the saw, the pile of boots, and amputated limbs. The somber music grows. And now, dammit, some jerk behind you starts telling his girlfriend the story!

It's like going to the movie theatre to see Kevin Costner. The music starts, the lights go dim, he's about to have his foot sawn off on a Civil War battlefield somewhere. You're really into this, what will happen? You see what he sees: the saw, the pile of boots, and amputated limbs. The somber music grows. And now, dammit, some jerk behind you starts telling his girlfriend the story! "He's going to pull his boot back on. And then he's going to go back to the battle where the Union line doesn't know what the hell to do; but neither does the Confederate. It's stalemate, someone has to make the first move—suicide really. So he's going to gallop into the open field and throw back his arms, begging gunfire. Like I said, suicide. But—"

"SHUT UP, YOU ASS!" you yell, spinning around. "Shut up and let the rest of us enjoy the show!"

Why do you yell? Because this jabbermouth is narrating. Just let the scene roll.

Like I said, I've learned to concede to Laura. Put it in scene. But if you want to keep it real, admit to making it up. Because, in reality, you're not. You're using an illusion of mirrors to reflect the very real truth.