MEMOIR #3: PICK AND CHOOSE

MEMOIR #3: PICK AND CHOOSE

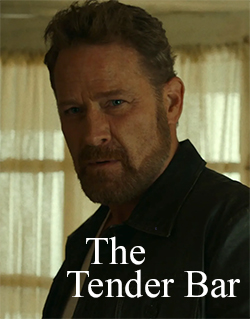

MEMOIR #3: PICK AND CHOOSEMEMOIR is not autobiography. Autobiographies are for famous people. Autobiographies rely on the facts of a person’s life to chronicle their journeys to fame, power, wealth, talent, and triumph—like Helen Keller in her The Story of My Life. Memoirs, however, use life to serve a larger theme or idea—like J. R. Moehringer in his memoir, made into film, The Tender Bar. The story is less about J.R. and more about his identity, a bigger issue that drove J. R.’s day-to-day.

Autobiography focuses on Joe Friday’s “just the facts, Ma’am.” Memoir relies on emotions and epiphany. Readers pick up memoir not because they care two hoots about the writer but because readers like what memoirists offer: universal themes and resolution to existential crises.

But it leaves me in writing a memoir with two major problems . . .

First, picking a single theme—difficult because there are so many, life is complex.

Second, choosing only those events in life which support that chosen thesis. What to say? What not to say?

FIRST: Picking the theme.

A fearful child, I grew up wary. I steered clear. My two sisters, one a year older and one a year younger, were not fearful by nature and did not suffer my trauma —though we all were cautioned by the leather belt hanging in a closet.

I wrote about that belt with its stinging whip, the pain cutting through my body to rattle my teeth, until one day I realized my mother was not the topic of my memoir. She'd become its scapegoat. I was horrified. She'd been under terrible duress in the '50s, caring for three healthy girls and a terminally ill child. Life and death spelled her hours; she had no patience for shenanigans and who could blame her? She was, in fact, heroic in her own right. Despite her stresses, she signed us up for art classes, gave us music and books, took us to the library and museums, Stanley Park in downtown Vancouver, and let us endlessly play. We built elaborate tent houses and she let us use Pablum and sugar water for our "teas." She took us visiting the old ladies in our neighborhood, netting us Arrowroot buscuits and an appreciation for aging fragilty. So not my nemesis.

After pages out to the recycle bin, I came to understand that the driving forces in my life were twofold: 1) I was by nature a fearful child, and 2) the Church with its inherent propensity for power and control had made minced-meat out of me. When I finally got two these thematics figured out, choosing what to include became easier.

SECOND: Choosing what experiences to include.

Just like a good photographer who tosses a thousand images to show off the one totally perfect picture—and thereby make a name for herself, so does a memoirist& toss a thousand (and ten thousand more) experiences to choose only those that showcase her thesis, and thereby tells an arresting tale.

Personally, having finally gotten my fearful nature and the church named as the "enemy," it should have been easy to pick events that created and fostered this guiding, driving theme of my life. Not necessarily. To explore my early fears, for instance, I began running on and on about the wonder of my school in order to& juxtaposition this nirvana against my anxiety over the male gender.

Above the wainscoting, Queen Elizabeth prevailed. She ran things here at James Park School the same way she did all of England and the Commonwealth—with quiet but watchful benevolence.

Opposite the Queen and the two lower classrooms, wide stairs went up to the second floor. Not ordinary stairs, these. They began at the middle of the hallway, four wide steps softened by thousands of feet, rising to a large, square landing, that branched to the right and to the left. Above the landing, two-story windows let in silver cloud or yellow sunlight. Sometimes, light dappled the planked floors below with shimmering mirrors; other times it painted the floorboards with chestnut hues.

I haven’t talked about the basement. For recess on sunny days, we lined up two by two to traipse outdoors in barely contained decorum, girls let loose on the lawn, boys into the oak trees or field out back. Nary the twain to meet, to my relief. Their rambunctious play distressed me; they were all over the place, I couldn’t settle. Sometimes, their threatening postures and bellicose taunting broke into brawls. The girls' basement nicely allowed me to relax. No boys to give alarm.

Two weeks into this dribble, I realized that my fear of boys is better demonstrated than narrated. Who cares about James Park School, however beautiful and hallowed it was? And lived in my mind. I cut the paragraphs to write:

Spring 1962 deepened and warmed. I started walking to Brownies. I’d leave right after supper and head for Patsy Patenaude’s, a mile away on New Westminster Ave., where we’d watch the Flintstones before continuing to Port Coquitlam’s pink civic auditorium. I’d just rounded the corner one evening, Coast Meridian to New West, proud of my new uniform, ironed, crisp, my Brownie pin attached to my tie—

Hey, little girl! I’m gonna stick your head in the ditch!

I jumped and stifled a scream. A grown boy emerged from the woods, half his face a torment of scars, and I stood transfixed by the brutality, the horrible disfigurement clawing down his neck into his shirt.

“Come here,” he called with a lurid smile, leaping the ditch ten feet away. “Gonna stick your head in the ditch and see your underpants!”

Pick and Choose.

I choose that scene.

I'm now at a place in my writing where I stand on pretty solid ground regarding my theses—fear and the church. I thus have a pretty good idea of what I'll include to showcase just how the church became an ill wind for someone like me, fearful, easily manipulated, God used as a weapon to extract compliance. Blowing me out to sea and dashing me hard against metaphorical rock cliffs. But thesis and supporting evidence is not the end all to a memoir. The writer's existential issues have to be resolved, Jospeh Cambpell's "hero within" made to rise.

THIRD: Resolution to existential crisis.

How did J. R. in The Tender Bar find his missing identity, his existential dilemma that drove him aimlessly through life?

How did J. R. in The Tender Bar find his missing identity, his existential dilemma that drove him aimlessly through life?

Spoiler alert. By finally seeking out his father, acknowledging his name to be Junior and not J. R., and then ultimately turning his deadbeat and violent dad into the police. This is what the memoir reader waits for. Decision. Action. Emotion and insight and realization! When his father knocked his girlfriend flat, baked chicken falling and sliding across the floor, J. R. understood who he was. He was not his father.

He seized control, became himself, found the hero within, and made the call—and became the writer he always wanted to be. Lucky for us.

A memoirist who told his tale—J. R. to Junior, back to J. R.

In my own case, how do I resolve my natural-born fear and the church's sin? No spoiler alert here. You can read it for yourself when it comes out. Or, like The Tender Bar, watch it on the big screen.

When Stones Cry Out.