The Tinsy Winsy Rag,

your monthly connect to this writer's life - and

always something

free & fun.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Tinsy Winsy and I hope you will not be disappointed!

Your first newsletter will arrive next month. In the meantime, please enjoy the many things I offer subscribers for free - including a pdf of my latest book, Taming the Dragons. Click here. Thank you.

Blog Subjects

- Alaskan Life

- Christian Nationalism

- On Writing

- Self-Publishing

- Book Design

- Christmas

- Narcissa

- Memoir

- Sweetbriar Illustrated

- Taming the Dragons

- Skagway AK Etc

- Guidepost Devotionals

- Living With Ravens

- Inspirational

- Christianity

- Reflection

- History - Women

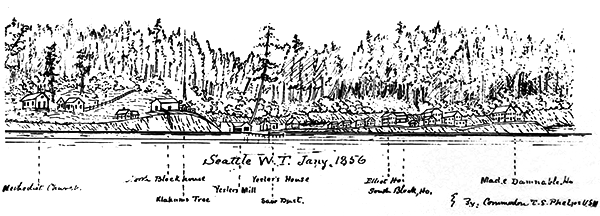

- History - Seattle

- History - Gold Rush

- History - Family

- Family

- Racism

- Sexual Assault

- Sexual Molestation

Recent Blogs

- Sackcloth and Ashes

- Why Deny Abuse in the Christian Community? PART I

- Giving FROM my Heart, Not Giving AWAY my Heart

- When the Bible is Weaponized

- The Call of the North: "B...bbbbbear."

Recommended Sites

• Fauzia Burke, Publicist• Jane Friedman, Marketing

• Laura Christianson, Platform

• Susy Flory, Memoir

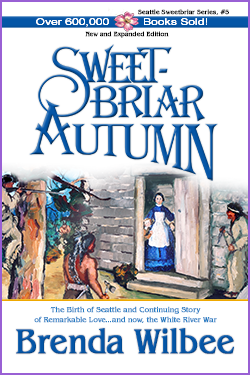

Sweetbriar Autumn #5 (out of print)

Seattle Sweetbriar Series

Published by Stewart Goodfellow Publishing

[NOTE: Not yet available. Please contact me—link below—to sign up for a notification notice.]

..........

Cover Design: Brenda Wilbee / Stewart Goodfellow Studio

........Interior Design:.Brenda Wilbee / Stewart Goodfellow Studio

.Front Cover Image: "Johnny King and Eliza Jones" by Mildred Schmidtman

..................................used by permission of her family

.................Sketches: © Brenda Wilbee

................ .......ISBN: 978-0-943777-24-5

.....................PRICE: 14.95 / paperback

.

.

.

Louisa Boren Denny knew as well as any that Seattle's merchants were slated to profit off the White River settlers this year. The fertile valley sixty miles upriver had proven magical, producing onions the size of small pumpkins, beets six inches wide, potatoes six and seven inches long and so plump it sometimes took two hands to pull them from the soil. The green beans, the settlers up there boasted, rivaled those of the fairytales. All a man had to do was plant a seed and get out of the way. Families like the Brannans and Kings stood to gain considerably, though the merchants in town stood to gain considerably more: Louisa and everyone else in town hadn't tasted a radish in years. She had her own garden, of course, they all did, but no one had the variety or size. A zucchini? She'd die for one of those. No, let's leave the hyperbole, she thought with a smile, to Ursula McConaha Wyckoff.

Louisa was a pretty woman, twenty-eight years old with raven black hair, light brown eyes, flawless skin. And still very much in love with her husband, David Denny, founder of Seattle; though David had become less vital to its development than his older brother Arthur, a principled man who'd inherited their father's political genius. At seventy-five years old and former legislator for both Indiana and Illinois, John Denny was now running for representative in the Oregon Territory. He and Louisa's mother (and the other Denny brothers) hadn't come up to Puget Sound after crossing the prairie, but instead had stayed in Oregon, where they collectively built the little town of Sublimity on the Willamette River.

"Stand still, you silly goose," Louisa said to her twenty-two-month-old daughter, who was determined to keep jumping. She'd just learned how to get both feet off the ground at the same time. "We’ll never get your hair tucked into your bonnet if you keep this up."

"Where my go?" the child asked, an articulate little girl with her own sense of syntax.

"To see Papa, and you need your bonnet."

"Why?"

Always "why" these days. "Because winter is coming, that's why."

"No! Why Papa leave his muss?"

It took her a second. "Oh, thermos! I don't know, does it matter?" This morning she was going to kill two birds with one stone. The night before, she'd broken her ceramic bread bowl. Knocked the table and down it went. If she could deliver the thermos and buy a new bowl, she might get back home in time scrub the floor before putting supper on. "Chin up now, darling!"

"Mama, that tickles!"

The girl finally bonneted and coat buttoned, Louisa shrugged into a heavy sweater and opened the door onto a crisp September morning. Emily darted out like a jack rabbit.

"Hey, wait for me!" Louisa swung her flour-sack handbag over a shoulder, thermos thudding against her ribs. She shut and latched the Dutch door and skirted the new rain barrel taking up half the porch of her "inside" house, the small board cabin she and David had built two years before, during Seattle's first Indian scare. They were recently back due to confirmed reports of escalating warfare east of the Cascade Mountains...and sporadic rumor suggesting that the Smalkamish, living this side of the mountain pass, might be in league. Would the murderous lot of them—and this was the question on everyone's mind—go after the unprotected settlers farming along White River?

"Emily Inez, we're not going to visit just now," she said, shaking her head in mock disapproval, for the little girl, waiting for no one, had bumped down the stairs on her bum and was halfway to Mary Ann's house next door.

"But my want to play!"

"I know you do. Perhaps on our way back."

They took their time on the three-block trail into town, Louisa eager to nurture in Emily a curiosity about the world. “This is a sword fern,” she explained, squatting to turn a feathery blade upside down and to show her daughter the tidy rows of spores beneath. “Do you see any more ferns?" she asked. "See how they grow all over the forest floor?”

“My see debbel cub.” She pointed.

“Yes, and devil’s club.” This was always a worry, Emily wandering off and getting caught in patch...and getting cut through by the spikes. “Oh, look, here’s a mushroom. No, we don’t eat these kind."

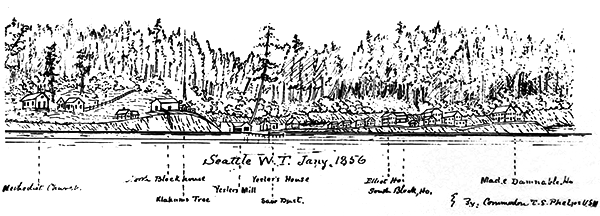

They passed a handful of houses hardly visible in the woods. Next, the cluttered Indian camp. Louisa paused to chat with Susan, Chief Curley's daughter. Finally the newly finished blockhouse on the right. A terrible eyesore. High walls of square-cut timber; two corner bastions, kidddy korner, at the roofline; surrounded by mud and stumps. But should they ever have to run for safety, God forbid, they couldn’t be stumbling through the forest. The trees had to come down and the brush burned. Still, an eyesore.

They passed a handful of houses hardly visible in the woods. Next, the cluttered Indian camp. Louisa paused to chat with Susan, Chief Curley's daughter. Finally the newly finished blockhouse on the right. A terrible eyesore. High walls of square-cut timber; two corner bastions, kidddy korner, at the roofline; surrounded by mud and stumps. But should they ever have to run for safety, God forbid, they couldn’t be stumbling through the forest. The trees had to come down and the brush burned. Still, an eyesore.

The trail transitioned into Front Street, angling slightly right and due south, dropping swiftly off the 12-foot cliff to sea level and to what everyone called "the Sawdust." Here stood Mr. Henry Yesler’s sawmill and cookhouse. The town proper, with its stores and shops, sat farther south, on "the Point," Doc Maynard's claim. The town popped up here because he sold his plats like yesterday's flapjacks, if not giving them away. The high whine of the whirling saws below, between Louisa and town, was its own flurried but orderly activity beneath the mill roof. Mr. Yesler operated two twelve-hour shifts, employing anyone who wanted to work, including the Duwamish—though he offered them only half pay, an injustice that stuck in Louisa's craw. Curley, Salmon Bay Charlie, Thlid, Suwalth, and several others worked alongside the regulars like Mr. Clarke and Mr. Butler and deserved better. David had hired on the day after they'd moved back to Seattle, hoping to mitigate some of the loss they'd suffer from not being able to work the homestead.

She caught sight of his toque, one she'd knit for him. He was part of a crew guiding a long section of a Douglas fir into the saw, its sharp blade biting through the wood, spewing sawdust, and spitting out one plank after another. A team of two men stood by to take the planks and stack them onto a measured pile of lumber. Other men burned trash, or hauled off the sawdust in squeaking wheelbarrows to the Point, where they dumped one load after another onto the tide flats.

A large cargo ship had tied up to the wharf. Sharp orders sang over the shrill, Yelser's longshoreman loading the vessel bound for San Francisco—and places like China, Australia, the Sandwich Islands. Ruffled with white caps, Elliot Bay glimmered. Louisa lifted a hand to better see through the brilliant sunlight bouncing off the water. A canoe was honing into shore. Three more, farther out, were having a rough time of it. Not surprising, given the wind. She readjusted her handbag, took Emily's hand, and descended into the hubbub.

David and Hillory Butler were hoisting a new section of Douglas fir into the saw trough. Saws still spinning, but making less noise, she approached. Someone jabbed David on the shoulder. He looked over and grinned. "Hang on a minute!" he hollered. Done, he hopped down off the platform, tossing off his gloves. His friend Salmon Bay Charlie leaned against a post, watching them, fishing from his shirt pocket cigarette papers and a tobacco tin.

"What's up?" David asked, angling Louisa away from the rumble.

"You forgot your thermos."

"I did, but you didn't have to come in. Plenty of coffee in the cookhouse."

"As good as mine?"

He laughed. "Well, hello there, peaches," he said to Emily and held out his arms. She all but flew at him.

"Too bad she doesn't like you," said Louisa, laughing.

David planted a dozen kisses on Emily's chin and neck, making her giggle. "Sorry I put you to all this trouble, Liza."

"I have to get a new bread bowl, remember?"

"Ah, yes, you do." He swung Emily onto his shoulders, to her shrieking delight. "Why don't you go down to the Doc's mercantile? I hear Mr. Van Asselt's been busy with his new lathe, making bowls, and Doc's selling them. Wooden," he added. "Can't break those." He reached for her hand, drew her in, and snuck a kiss. "You could have a visit with Catherine," he said, referring to Doc Maynard's wife. "She can show you the bowls."

"Maybe I will." She shrugged off the handbag and rummaged for the thermos.

"Ready to get down?" David asked Emily, tipping his head back to see her, of course throwing her backward.

"Papa! My fall!" she screamed, jerking forward and hunching over his head, fiercely tightening her grip on his forehead to counter her balance.

"No you won't, little walnut! Not unless I dump you like this," he crowed, grabbing her ankles and twisting sideways, and then swinging her around upside down to the tune of shrieks and screams and thrilling laughter. He caught her up in his arms and gave her a kiss.

"The Indians are coming!"

Shivers shot down Louisa's spine.

Ninety miles southeast of Seattle as the rivers wind, and nestled in the foothills of the Cascade Mountain Range, Allen Porter knew he'd be the first to be molested when the Yakima came through. His farm sat just inside the high, narrow Naches Pass, near the headwaters of White River in a picturesque Indian pasture everyone called Porter's Prairie. Stretching downriver sixteen miles away were other claims, all the way to Mox La Push where the White and Black Rivers converged and vanished into the slow-moving Duwamish. When Porter learned the brutal fate of two Mox La Push men who'd gone into Yakima country last summer, he'd begun looking over his shoulder wherever he went and sleeping with two loaded pistols at his bedside. But when news came on September 23rd, 1855, that the Yakima had murdered their Indian agent, Porter could no longer content himself with a wary eye and ready fire. He took to sleeping in a cedar-bough shelter at the forest edge, 200 feet from his cabin. He did not want his throat slit while asleep.

Ninety miles southeast of Seattle as the rivers wind, and nestled in the foothills of the Cascade Mountain Range, Allen Porter knew he'd be the first to be molested when the Yakima came through. His farm sat just inside the high, narrow Naches Pass, near the headwaters of White River in a picturesque Indian pasture everyone called Porter's Prairie. Stretching downriver sixteen miles away were other claims, all the way to Mox La Push where the White and Black Rivers converged and vanished into the slow-moving Duwamish. When Porter learned the brutal fate of two Mox La Push men who'd gone into Yakima country last summer, he'd begun looking over his shoulder wherever he went and sleeping with two loaded pistols at his bedside. But when news came on September 23rd, 1855, that the Yakima had murdered their Indian agent, Porter could no longer content himself with a wary eye and ready fire. He took to sleeping in a cedar-bough shelter at the forest edge, 200 feet from his cabin. He did not want his throat slit while asleep.

Four days later, on September 27th, he discovered his cattle missing. A day's search rendered nothing and he climbed into his lair that night irritably perturbed. He'd call on the Smalkamish in the morning, see what they had to say about it. Blackguards. This would not be their first fiery exchange of words. Always clamoring about their land rights. Take it up with Governor Stevens, was his position.

He fell into an exhausted sleep despite his irritation...but then woke, heart racing. Freezing cold it was when he poked his head out of his temporary shelter, winter around the corner and so much work yet to be done. He shivered involuntarily. The moon held little light, and only with difficulty could he locate the hazy rooflines of his house and barn. Was this imagination? Or had he just seen someone move? Visitors was his first thought. But who would come by at such an hour? Perhaps they needed shelter?

Steeling himself, he cut across the backfield and was coming up alongside the barn when it came to him that these were no ordinary visitors; they were strategically placing themselves around his house. Clutching his rifle and bent over at the waist, he darted forward. Dart and duck. He kept at it until finally he gained the barn's shadow. Catching his breath in short, suppressed gusts, he edged up to the far comer and carefully peered around. He snapped back, heart pounding, shoulders to the wall. Indians! Everything he feared!

Furtively, and without waiting another second, he headed swiftly and as silently as he could for the woods, though he did not go in. He ran the edge, dodging into the forest growth every few yards to determine if anyone had spotted him. Halfway to the river, he checked again. Flames danced out his windows and licked along the roofline of his house in tongues of yellow and orange. Horrified, he turned and ran, gasping for breath, sweat stinging his eyes. At the river he dropped his rifle on the sandy beach, flipped his heavy canoe, tossed in his gun, and threw in his right foot, seizing the gunwales with hands, and pushed off. Quickly he drew in his other foot and scooted, flat on his back, down along the boat's narrow bottom. If the Indians spotted him, they might think his canoe had simply worked loose from its mooring.

Hands clasped like a dead man over his chest, he began to count to the fierce pounding of his heart. One-two-thee... At twenty he’d sit up and paddle like the devil, stopping only to warn his neighbors. At the count of ten he heard an owl. At fifteen, another owl. At eighteen he bolted straight up, heart in his throat—a knee-jerk reaction to the bloodcurdling war cry ripping through the night, about stopping his heart and nearly wrenching off his ears. He scrambled onto his knees, canoe rocking. His house was entirely engulfed and now his barn threw off a fiery glow. He grabbed his paddle and dug in.

Down the river he raced against time. First Will Brannan. Then Harvey Jones. George King. Robert Beatty. John Thomas. Moses Kirkland. Sam Russell. Mr. Thompson. Enos Cooper. David Neeley. He lost count. The night at it's darkest hour, he reached Mox La Push. Joseph Fanjoy, upon opening his door dressed only in red flannel longjohns and taking one look at Porter in rags and bloody with scratches, hollered off his shoulder, "Laura, get up, we have company!"

Fanjoy and his wife hauled him indoors and set him in a rocking chair. "No," he protested, but when he went to stand, he teetered and dropped back into the chair with a hard slam.

"Look at ye, man! Yer a bloody mess, on yer last leg! Ye can't even find yer own feet. Here," and Fanjoy shoved a flask of whiskey into his hands, which he gratefully took, "it'll calm ye down."

They talked him into sleeping a few hours. Terrified as he was, he agreed. If the Indians didn't get him, he'd surely drown, too weary to handle the canoe. Besides, his nerves were too frayed to go on, his legs too numb, too wobbly to get out of his canoe one more time and stumble yet again up to another house, his voice too hoarse to rasp out one more time, "The Indians are corning!"

"There's been no sign of trouble here, Porter," assured Fanjoy. "You must get some sleep."

He slept but two hours, sunlight barely nudging back the night when he took off. Fanjoys would take over warning the Duwamish settlers. He could take a straight shot to Seattle.

But it was midmorning before he rounded out of the Duwamish River mouth into Elliott Bay. Five miles to the northeast, across the water, was Seattle. Another hour, he thought, if the tide right. Maybe two because of the wind. With fresh determination, he set to, ignoring the fire in his joints, the knifing pain in his muscles, the blood on his hands. Finally, fifty yards out and feeling near dead, he hollered, “The Indians are coming!”

It came out like a whisper.

"The Indians are coming!"

Shivers shot down Louisa's spine. She and David blinked at each other, stunned, then pivoted. Mill workers jumped off the mill platform and ran pell mell for the beach. Allen Porter! He says the Indians are coming!

"Can we get some help down here?" someone bellowed.

David seized her hand. A strange kind of wild cold roiled from her belly to her extremities; numb all over, she could hardly keep up. But it was a short run. Thirty seconds and they were at the beach, panting hard. David dragged her through the millhands. Behind them, people from town and down by the tannery came running. "Oh dear God," she gasped. Mr. Porter from White River, his clothes in shreds, his exposed limbs and face lacerated almost beyond recognition, had collapsed in hysterical exhaustion against the gunwales of his canoe. Panting and wheezing and in a terrible state of shock, he blathered incoherently of a perilous escape from the Indians. Louisa glanced off her shoulder, shivering, alert to danger. Emily wailed, "Papa, Papa! What happening?"

"Nothing for you to worry about, pumpkin."

"The man has owies!" She shoved her face into his shoulder, and quickly he buttoned her into his coat so she couldn't see.

Doc Maynard burst onto the scene, dropped to a squat at the bow of the dugout. "Give him some room!" he ordered. They all stood back, pushing up against a gathering crowd. "Slow down, slow down," said Doc. "They burned your barn? No? Your house?"

“Both...and stole my cattle.”

"Let's get you out of here," said Doc, "and up to the cookhouse." He and Dexter Horton hauled Mr. Porter's dugout another foot clear of the water and together managed to get him out of the canoe without getting themselves too wet. Porter's knees gave way, though, and he would have dropped to the shingle but for Doc Maynard.

"I can't feel my legs," he gasped.

"You've been sitting on them for hours. Of course you can't. Paddling all that way from the pass makes you more dead than alive. Wyckoff!" he hollered to the blacksmith. "Help us get him up to the cookhouse! We can clean him up and see if there’s anything left to save. Catherine," he called, looking around for his wife, "go home and get my kit, I'm going to need you. And if any of you can spare a blanket, we''ll need dozens if what Porters says is true. Now!" he snapped, and off ran Ursula McConaha Wyckoff, Sarah Yesler, and Kate Blaine. Louisa herself couldn't move.These were the canoes she'd seen.

"This is no place for Emily, I'm taking her to Anna's," said David. "No, you stay here. Plenty of men to help out, but the children are going to need a woman to comfort them. Liza, no, I'll be back as soon as I can."

"But what's happening to us all, David?"

"Nothing we can't handle."

It was then she noticed the quiet. Yesler had shut down the saws and three more canoes were coming in. The Cox family and Mr. Lake, someone said.

They arrived in similar exhaustion, though more coherent and unscratched. Three millhands pulled their dugouts up and then escorted Mr. Lake and Mr. and Mrs. Cox to the cookhouse, followed by Catherine Butler who'd just arrived wiping her hands on her apron, and who was now chatting to distract the frightened children. Next in was Moses Kirkland and his daughters, all four girls shivering and sniffling and breaking into sobs when lifted free of their two canoes. Half a mile out, another canoe rode dangerously low in the water and seemed to come in at a zigzag, veering south, then north, sometimes going in circles.

"Someone better go get them," said Judge Lander. Hillory Butler and his friend Jives jumped into one of Mr. Kirkland's canoes and shoved off. The sawmill whistle went off with a shriek, scaring them all. It blasted two more times, then fell silent. Signal for everyone: trouble on the Sawdust. Arthur, Louisa's brother-in-law, and Henry Yesler, the sawmill owner, pushed through the crowd. Yesler stepped up on a log, arm up for silence.

"This is what we know so far!" he said, projecting his voice so the growing crowd could hear. "Mr. Porter reports that the Indians are on the warpath. He's warned everyone he could coming down the river, so we're looking at maybe a dozen families, perhaps a dozen bachelors arriving in a similar state. He did say he slept a couple of hours in Mox La Push, but that when he passed the Collins' farm this morning, he noticed several canoes beached near the house. Not, however, the hostile Indians he feared. These were the canoes of the Coxes, Joe Lake, and Moses Kirkland—and the Brannan, King, and Joneses familes coming in now. They'd stopped for the night. I understand that the Brannans and Joneses have babies. Let's get them up to the cookhouse as quickly as possible. Once Doc assesses their state of mind and health, we'll begin organizing how to help the others still to arrive. Arthur will give you the details," he said, turning it over to Louisa's brother-in-law, "of what we've been able to work out so far."

"There is no need to panic!" Arthur announced, leaping onto the log beside Yesler. For once, Louisa felt proud of him, and felt herself calm down. He was, if nothing else, a man in charge. "We're sending someone right now to Ft. Steilacoom to give notice of what's happening, but for now we will assume this dog's bark is far worse than his bite. Our Indian friends have heard nothing of the Yakima crossing the pass. We're probably looking at local hostility—more easily diffused. Curley and Suwalth have already agreed to go up and speak with the Smalkamish. As to our own position, we're secure. We have the blockhouses and volunteer militia. And there’s strength in numbers.

"Our priority, then, is to help those coming in with nothing but the clothes on their backs, and do what we can to alleviate their suffering. Which brings us to the need for shelter. Latimer's Boarding House and Captain Felker's House have limited room.“ Louisa glanced first to her uncle's place on the Sawdust and then to the Point where the captain's white, two-story hotel sat on the bluff. "Dexter Horton and I have agreed to provide tents from our store and Mr. Yesler's agreed to let them camp on the Sawdust. Williamson?" he asked, scanning the crowd. Dr. Williamson raised his hand. "You willing to do the same?"

"Sure not going to let you have all the fun! Let's make it a competition! I'll even throw in free coffee pots! And coffee!"

Shakey laughter broke out and Arthur blushed. "I suppose Horton and I can step up. Plenty of last summer's gold-mining kits sitting on our back shelf!"

"Hear, hear!"

"Huzzah! Huzzah!"

"It's preferable, of course," urged Arthur, "to open our own homes. Camping on the Sawdust at this time of year is no picnic. So if you know anyone from White River, or if you're willing to take in strangers, let Mrs. Yesler know. She's organizing everything. It would help, too, if the women could put together some victuals. These poeple are famished."

I bet they are, thought Lousia. Luther Collins was not a man to offer food to overnight guests.

"This is all for now, until we know more!" Arthur stepped off the log.

"In the meantime," announced Yesler, "the mill is closed until we know what we're looking at!" He too stepped off the log; and he and Arthur headed to the cookhouse, bypassing David.

"Emily's okay?" Lousia asked before he could fully spot her. He pushed through and took her by the elbow. "Yes. I first took her to Anna's, but Dobbins is back.."

"Since when?"

"Since last night. Anyway, I didn't want to leave her there. She doesn't need to be part of their rows. So she's over at Mary Ann's, happy as a clam. Oh, that doesn't look good," he said, pointing his chin toward the water and tandum canoes struggling offshore.

"Better than it did," said Louisa. "I thought for sure they'd both going under when Mr. Butler tried hitching their painter to his stern."

David watched for a moment as Butler and Jives hauled hard on their paddles, dragging in a nearly swamped canoe—the Joneses, someone confirmed. Faces pinched and strained, fingers white-knuckled on the gunwales, mother and father spent what little strength they had tyring to comfort their children.

"They've taken on a boatload of water!" called Mr. Butler when he reached fifty yards out. Five feet out, David and two others plunged into the ocean water to wade past Butler and Jives to angle in the half-submerged dugout...and the distressed Jones family. Butler and Jives managed to beach their own canoe and then splattered over to help, all five men hard pressed to nose the nearly submerged dugout onto the shingle, seawater sloshing. It ground to a stop, stern swinging, tipped sideways and dumped water over the gunwales. Mrs. Jones let out a startled scream, baby crying. Butler and Jives fell backwards onto the sand, so played out they couldn't get up. Mr. Jones, with the last of his energy, flung himself free of the canoe and tried to haul the canoe farther up onto the beach, but fell. He lay panting and shivering on the wet sand. "Get my wife, my poor children," he begged, holding his chest, and blinking his eyes..

Mr. Bettman already had Mrs. Jones out of the watery, tippy canoe and was carrying her, a tiny woman in shock, up to the tideline. David and Frank Matthias were dragging the canoe onto the beach, easier now that most of the water had drained, while Louisa's uncle, Hugh Latimer, side-stepped alongside, waiting just long enough for the canoe to clear the water before plucking up six-year-old Johnny King and his four-and-a-half-year-old half sister, both children blue and shivering and soaking wet, Olivia wailing. Louisa reached down to get two-year-old Percival, but he was tied into a crate securely fastened to a thwart. She dropped to her knees and tore at the wet, swollen ties that held the boy, blue and violently shivering. He suddenly stopped crying and stared up at her, chin jumping, the blonde coils of his hair dripping seawater into his face. Emily's age. She blinked back hot, stinging tears. She must get him indoors before he caught his death, if he hadn't already.

"Let me help." Abigail Holgate squatted beside Louisa, and gratefully Louisa let the widow take over; though she too struggled. She finally got the knots loose and snatched up the boy, opening her coat around him and giving a short, quick squeal of shock when the frigid seawater went straight through to her skin. "I'll take him, Louisa dear. There's another canoe about to come in." She hustled over the shingle to his stricken mother just in time to break Lizzie Jones' fall before she landed in a faint on the seaweed.

"Hoy! I need some help over here!"

Louisa whirled. Two men and a woman, and apparently the other baby. Tom Russell, the sheriff, was trying to heave one of the men to his feet. His wife was pleading to the woman, still in the canoe, to hand over her infant. David had squatted beside the second man, sprawled on his stomach, one leg still caught in the canoe. "Bill is it?" he aked.

"Will. Will Brannan."

"Will, can you walk a couple hundred yards?"

"I don't know, I can't find my legs. Give me a hand and we'll see."

Louisa skirted around and dropped to her knees beside the Nancy Russell and the crazed woman whimpering "no, no. No, it's to late, she's dead, I tell you she's dead." Louisa reached in to feel for a pulse, horrified at how cold and wet the baby was. "She's alive! Quickly, you must give her to me, Mrs. Brannan. You must!"

"No!"

Without thinking, Louisa smacked Mrs. Brannan's face, hard. Startled, she reached to touch her cheek and Louisa, taking opportunity, seized the six-month-old infant and ran. Dear God, don't let this baby die! she prayed, frantically wrapping it with her heavy sweater and gasping, like Widow Holgate, from the cold. She burst through the cookhouse door. A chaotic scene. "Doc! Doc!"

And that's how the Brannans came to stay with Louisa and David, everyone crammed into their "inside" house. Not an unhappy arrangement, though the uncertain days passed slowly, everyone waiting for the return of Curley and Suwalth. As for Bonnie Brannan's recovery, everyone took turns sealing her in warmth and love, passing her from one loving embrace to another. No one even thought of the thermos. Dropped somewhere and gone.

..........

Cover Design: Brenda Wilbee / Stewart Goodfellow Studio

........Interior Design:.Brenda Wilbee / Stewart Goodfellow Studio

.Front Cover Image: "Johnny King and Eliza Jones" by Mildred Schmidtman

..................................used by permission of her family

.................Sketches: © Brenda Wilbee

................ .......ISBN: 978-0-943777-24-5

.....................PRICE: 14.95 / paperback

.

.

.

CHAPTER 1

illustrated and expanded edition

| All accounts of Seattle's part in the Indian War begin with the experience of Allen L. Porter of White River.

—Roberta Frye Watt, Katy Denny's daughter in Four Wagons West

|

Louisa was a pretty woman, twenty-eight years old with raven black hair, light brown eyes, flawless skin. And still very much in love with her husband, David Denny, founder of Seattle; though David had become less vital to its development than his older brother Arthur, a principled man who'd inherited their father's political genius. At seventy-five years old and former legislator for both Indiana and Illinois, John Denny was now running for representative in the Oregon Territory. He and Louisa's mother (and the other Denny brothers) hadn't come up to Puget Sound after crossing the prairie, but instead had stayed in Oregon, where they collectively built the little town of Sublimity on the Willamette River.

"Stand still, you silly goose," Louisa said to her twenty-two-month-old daughter, who was determined to keep jumping. She'd just learned how to get both feet off the ground at the same time. "We’ll never get your hair tucked into your bonnet if you keep this up."

"Where my go?" the child asked, an articulate little girl with her own sense of syntax.

"To see Papa, and you need your bonnet."

"Why?"

Always "why" these days. "Because winter is coming, that's why."

"No! Why Papa leave his muss?"

It took her a second. "Oh, thermos! I don't know, does it matter?" This morning she was going to kill two birds with one stone. The night before, she'd broken her ceramic bread bowl. Knocked the table and down it went. If she could deliver the thermos and buy a new bowl, she might get back home in time scrub the floor before putting supper on. "Chin up now, darling!"

"Mama, that tickles!"

The girl finally bonneted and coat buttoned, Louisa shrugged into a heavy sweater and opened the door onto a crisp September morning. Emily darted out like a jack rabbit.

"Hey, wait for me!" Louisa swung her flour-sack handbag over a shoulder, thermos thudding against her ribs. She shut and latched the Dutch door and skirted the new rain barrel taking up half the porch of her "inside" house, the small board cabin she and David had built two years before, during Seattle's first Indian scare. They were recently back due to confirmed reports of escalating warfare east of the Cascade Mountains...and sporadic rumor suggesting that the Smalkamish, living this side of the mountain pass, might be in league. Would the murderous lot of them—and this was the question on everyone's mind—go after the unprotected settlers farming along White River?

"Emily Inez, we're not going to visit just now," she said, shaking her head in mock disapproval, for the little girl, waiting for no one, had bumped down the stairs on her bum and was halfway to Mary Ann's house next door.

"But my want to play!"

"I know you do. Perhaps on our way back."

They took their time on the three-block trail into town, Louisa eager to nurture in Emily a curiosity about the world. “This is a sword fern,” she explained, squatting to turn a feathery blade upside down and to show her daughter the tidy rows of spores beneath. “Do you see any more ferns?" she asked. "See how they grow all over the forest floor?”

“My see debbel cub.” She pointed.

“Yes, and devil’s club.” This was always a worry, Emily wandering off and getting caught in patch...and getting cut through by the spikes. “Oh, look, here’s a mushroom. No, we don’t eat these kind."

The trail transitioned into Front Street, angling slightly right and due south, dropping swiftly off the 12-foot cliff to sea level and to what everyone called "the Sawdust." Here stood Mr. Henry Yesler’s sawmill and cookhouse. The town proper, with its stores and shops, sat farther south, on "the Point," Doc Maynard's claim. The town popped up here because he sold his plats like yesterday's flapjacks, if not giving them away. The high whine of the whirling saws below, between Louisa and town, was its own flurried but orderly activity beneath the mill roof. Mr. Yesler operated two twelve-hour shifts, employing anyone who wanted to work, including the Duwamish—though he offered them only half pay, an injustice that stuck in Louisa's craw. Curley, Salmon Bay Charlie, Thlid, Suwalth, and several others worked alongside the regulars like Mr. Clarke and Mr. Butler and deserved better. David had hired on the day after they'd moved back to Seattle, hoping to mitigate some of the loss they'd suffer from not being able to work the homestead.

She caught sight of his toque, one she'd knit for him. He was part of a crew guiding a long section of a Douglas fir into the saw, its sharp blade biting through the wood, spewing sawdust, and spitting out one plank after another. A team of two men stood by to take the planks and stack them onto a measured pile of lumber. Other men burned trash, or hauled off the sawdust in squeaking wheelbarrows to the Point, where they dumped one load after another onto the tide flats.

A large cargo ship had tied up to the wharf. Sharp orders sang over the shrill, Yelser's longshoreman loading the vessel bound for San Francisco—and places like China, Australia, the Sandwich Islands. Ruffled with white caps, Elliot Bay glimmered. Louisa lifted a hand to better see through the brilliant sunlight bouncing off the water. A canoe was honing into shore. Three more, farther out, were having a rough time of it. Not surprising, given the wind. She readjusted her handbag, took Emily's hand, and descended into the hubbub.

David and Hillory Butler were hoisting a new section of Douglas fir into the saw trough. Saws still spinning, but making less noise, she approached. Someone jabbed David on the shoulder. He looked over and grinned. "Hang on a minute!" he hollered. Done, he hopped down off the platform, tossing off his gloves. His friend Salmon Bay Charlie leaned against a post, watching them, fishing from his shirt pocket cigarette papers and a tobacco tin.

"What's up?" David asked, angling Louisa away from the rumble.

"You forgot your thermos."

"I did, but you didn't have to come in. Plenty of coffee in the cookhouse."

"As good as mine?"

He laughed. "Well, hello there, peaches," he said to Emily and held out his arms. She all but flew at him.

"Too bad she doesn't like you," said Louisa, laughing.

David planted a dozen kisses on Emily's chin and neck, making her giggle. "Sorry I put you to all this trouble, Liza."

"I have to get a new bread bowl, remember?"

"Ah, yes, you do." He swung Emily onto his shoulders, to her shrieking delight. "Why don't you go down to the Doc's mercantile? I hear Mr. Van Asselt's been busy with his new lathe, making bowls, and Doc's selling them. Wooden," he added. "Can't break those." He reached for her hand, drew her in, and snuck a kiss. "You could have a visit with Catherine," he said, referring to Doc Maynard's wife. "She can show you the bowls."

"Maybe I will." She shrugged off the handbag and rummaged for the thermos.

"Ready to get down?" David asked Emily, tipping his head back to see her, of course throwing her backward.

"Papa! My fall!" she screamed, jerking forward and hunching over his head, fiercely tightening her grip on his forehead to counter her balance.

"No you won't, little walnut! Not unless I dump you like this," he crowed, grabbing her ankles and twisting sideways, and then swinging her around upside down to the tune of shrieks and screams and thrilling laughter. He caught her up in his arms and gave her a kiss.

"The Indians are coming!"

Shivers shot down Louisa's spine.

Four days later, on September 27th, he discovered his cattle missing. A day's search rendered nothing and he climbed into his lair that night irritably perturbed. He'd call on the Smalkamish in the morning, see what they had to say about it. Blackguards. This would not be their first fiery exchange of words. Always clamoring about their land rights. Take it up with Governor Stevens, was his position.

He fell into an exhausted sleep despite his irritation...but then woke, heart racing. Freezing cold it was when he poked his head out of his temporary shelter, winter around the corner and so much work yet to be done. He shivered involuntarily. The moon held little light, and only with difficulty could he locate the hazy rooflines of his house and barn. Was this imagination? Or had he just seen someone move? Visitors was his first thought. But who would come by at such an hour? Perhaps they needed shelter?

Steeling himself, he cut across the backfield and was coming up alongside the barn when it came to him that these were no ordinary visitors; they were strategically placing themselves around his house. Clutching his rifle and bent over at the waist, he darted forward. Dart and duck. He kept at it until finally he gained the barn's shadow. Catching his breath in short, suppressed gusts, he edged up to the far comer and carefully peered around. He snapped back, heart pounding, shoulders to the wall. Indians! Everything he feared!

Furtively, and without waiting another second, he headed swiftly and as silently as he could for the woods, though he did not go in. He ran the edge, dodging into the forest growth every few yards to determine if anyone had spotted him. Halfway to the river, he checked again. Flames danced out his windows and licked along the roofline of his house in tongues of yellow and orange. Horrified, he turned and ran, gasping for breath, sweat stinging his eyes. At the river he dropped his rifle on the sandy beach, flipped his heavy canoe, tossed in his gun, and threw in his right foot, seizing the gunwales with hands, and pushed off. Quickly he drew in his other foot and scooted, flat on his back, down along the boat's narrow bottom. If the Indians spotted him, they might think his canoe had simply worked loose from its mooring.

Hands clasped like a dead man over his chest, he began to count to the fierce pounding of his heart. One-two-thee... At twenty he’d sit up and paddle like the devil, stopping only to warn his neighbors. At the count of ten he heard an owl. At fifteen, another owl. At eighteen he bolted straight up, heart in his throat—a knee-jerk reaction to the bloodcurdling war cry ripping through the night, about stopping his heart and nearly wrenching off his ears. He scrambled onto his knees, canoe rocking. His house was entirely engulfed and now his barn threw off a fiery glow. He grabbed his paddle and dug in.

Down the river he raced against time. First Will Brannan. Then Harvey Jones. George King. Robert Beatty. John Thomas. Moses Kirkland. Sam Russell. Mr. Thompson. Enos Cooper. David Neeley. He lost count. The night at it's darkest hour, he reached Mox La Push. Joseph Fanjoy, upon opening his door dressed only in red flannel longjohns and taking one look at Porter in rags and bloody with scratches, hollered off his shoulder, "Laura, get up, we have company!"

Fanjoy and his wife hauled him indoors and set him in a rocking chair. "No," he protested, but when he went to stand, he teetered and dropped back into the chair with a hard slam.

"Look at ye, man! Yer a bloody mess, on yer last leg! Ye can't even find yer own feet. Here," and Fanjoy shoved a flask of whiskey into his hands, which he gratefully took, "it'll calm ye down."

They talked him into sleeping a few hours. Terrified as he was, he agreed. If the Indians didn't get him, he'd surely drown, too weary to handle the canoe. Besides, his nerves were too frayed to go on, his legs too numb, too wobbly to get out of his canoe one more time and stumble yet again up to another house, his voice too hoarse to rasp out one more time, "The Indians are corning!"

"There's been no sign of trouble here, Porter," assured Fanjoy. "You must get some sleep."

He slept but two hours, sunlight barely nudging back the night when he took off. Fanjoys would take over warning the Duwamish settlers. He could take a straight shot to Seattle.

But it was midmorning before he rounded out of the Duwamish River mouth into Elliott Bay. Five miles to the northeast, across the water, was Seattle. Another hour, he thought, if the tide right. Maybe two because of the wind. With fresh determination, he set to, ignoring the fire in his joints, the knifing pain in his muscles, the blood on his hands. Finally, fifty yards out and feeling near dead, he hollered, “The Indians are coming!”

It came out like a whisper.

"The Indians are coming!"

Shivers shot down Louisa's spine. She and David blinked at each other, stunned, then pivoted. Mill workers jumped off the mill platform and ran pell mell for the beach. Allen Porter! He says the Indians are coming!

"Can we get some help down here?" someone bellowed.

David seized her hand. A strange kind of wild cold roiled from her belly to her extremities; numb all over, she could hardly keep up. But it was a short run. Thirty seconds and they were at the beach, panting hard. David dragged her through the millhands. Behind them, people from town and down by the tannery came running. "Oh dear God," she gasped. Mr. Porter from White River, his clothes in shreds, his exposed limbs and face lacerated almost beyond recognition, had collapsed in hysterical exhaustion against the gunwales of his canoe. Panting and wheezing and in a terrible state of shock, he blathered incoherently of a perilous escape from the Indians. Louisa glanced off her shoulder, shivering, alert to danger. Emily wailed, "Papa, Papa! What happening?"

"Nothing for you to worry about, pumpkin."

"The man has owies!" She shoved her face into his shoulder, and quickly he buttoned her into his coat so she couldn't see.

Doc Maynard burst onto the scene, dropped to a squat at the bow of the dugout. "Give him some room!" he ordered. They all stood back, pushing up against a gathering crowd. "Slow down, slow down," said Doc. "They burned your barn? No? Your house?"

“Both...and stole my cattle.”

"Let's get you out of here," said Doc, "and up to the cookhouse." He and Dexter Horton hauled Mr. Porter's dugout another foot clear of the water and together managed to get him out of the canoe without getting themselves too wet. Porter's knees gave way, though, and he would have dropped to the shingle but for Doc Maynard.

"I can't feel my legs," he gasped.

"You've been sitting on them for hours. Of course you can't. Paddling all that way from the pass makes you more dead than alive. Wyckoff!" he hollered to the blacksmith. "Help us get him up to the cookhouse! We can clean him up and see if there’s anything left to save. Catherine," he called, looking around for his wife, "go home and get my kit, I'm going to need you. And if any of you can spare a blanket, we''ll need dozens if what Porters says is true. Now!" he snapped, and off ran Ursula McConaha Wyckoff, Sarah Yesler, and Kate Blaine. Louisa herself couldn't move.These were the canoes she'd seen.

"This is no place for Emily, I'm taking her to Anna's," said David. "No, you stay here. Plenty of men to help out, but the children are going to need a woman to comfort them. Liza, no, I'll be back as soon as I can."

"But what's happening to us all, David?"

"Nothing we can't handle."

It was then she noticed the quiet. Yesler had shut down the saws and three more canoes were coming in. The Cox family and Mr. Lake, someone said.

They arrived in similar exhaustion, though more coherent and unscratched. Three millhands pulled their dugouts up and then escorted Mr. Lake and Mr. and Mrs. Cox to the cookhouse, followed by Catherine Butler who'd just arrived wiping her hands on her apron, and who was now chatting to distract the frightened children. Next in was Moses Kirkland and his daughters, all four girls shivering and sniffling and breaking into sobs when lifted free of their two canoes. Half a mile out, another canoe rode dangerously low in the water and seemed to come in at a zigzag, veering south, then north, sometimes going in circles.

"Someone better go get them," said Judge Lander. Hillory Butler and his friend Jives jumped into one of Mr. Kirkland's canoes and shoved off. The sawmill whistle went off with a shriek, scaring them all. It blasted two more times, then fell silent. Signal for everyone: trouble on the Sawdust. Arthur, Louisa's brother-in-law, and Henry Yesler, the sawmill owner, pushed through the crowd. Yesler stepped up on a log, arm up for silence.

"This is what we know so far!" he said, projecting his voice so the growing crowd could hear. "Mr. Porter reports that the Indians are on the warpath. He's warned everyone he could coming down the river, so we're looking at maybe a dozen families, perhaps a dozen bachelors arriving in a similar state. He did say he slept a couple of hours in Mox La Push, but that when he passed the Collins' farm this morning, he noticed several canoes beached near the house. Not, however, the hostile Indians he feared. These were the canoes of the Coxes, Joe Lake, and Moses Kirkland—and the Brannan, King, and Joneses familes coming in now. They'd stopped for the night. I understand that the Brannans and Joneses have babies. Let's get them up to the cookhouse as quickly as possible. Once Doc assesses their state of mind and health, we'll begin organizing how to help the others still to arrive. Arthur will give you the details," he said, turning it over to Louisa's brother-in-law, "of what we've been able to work out so far."

"There is no need to panic!" Arthur announced, leaping onto the log beside Yesler. For once, Louisa felt proud of him, and felt herself calm down. He was, if nothing else, a man in charge. "We're sending someone right now to Ft. Steilacoom to give notice of what's happening, but for now we will assume this dog's bark is far worse than his bite. Our Indian friends have heard nothing of the Yakima crossing the pass. We're probably looking at local hostility—more easily diffused. Curley and Suwalth have already agreed to go up and speak with the Smalkamish. As to our own position, we're secure. We have the blockhouses and volunteer militia. And there’s strength in numbers.

"Our priority, then, is to help those coming in with nothing but the clothes on their backs, and do what we can to alleviate their suffering. Which brings us to the need for shelter. Latimer's Boarding House and Captain Felker's House have limited room.“ Louisa glanced first to her uncle's place on the Sawdust and then to the Point where the captain's white, two-story hotel sat on the bluff. "Dexter Horton and I have agreed to provide tents from our store and Mr. Yesler's agreed to let them camp on the Sawdust. Williamson?" he asked, scanning the crowd. Dr. Williamson raised his hand. "You willing to do the same?"

"Sure not going to let you have all the fun! Let's make it a competition! I'll even throw in free coffee pots! And coffee!"

Shakey laughter broke out and Arthur blushed. "I suppose Horton and I can step up. Plenty of last summer's gold-mining kits sitting on our back shelf!"

"Hear, hear!"

"Huzzah! Huzzah!"

"It's preferable, of course," urged Arthur, "to open our own homes. Camping on the Sawdust at this time of year is no picnic. So if you know anyone from White River, or if you're willing to take in strangers, let Mrs. Yesler know. She's organizing everything. It would help, too, if the women could put together some victuals. These poeple are famished."

I bet they are, thought Lousia. Luther Collins was not a man to offer food to overnight guests.

"This is all for now, until we know more!" Arthur stepped off the log.

"In the meantime," announced Yesler, "the mill is closed until we know what we're looking at!" He too stepped off the log; and he and Arthur headed to the cookhouse, bypassing David.

"Emily's okay?" Lousia asked before he could fully spot her. He pushed through and took her by the elbow. "Yes. I first took her to Anna's, but Dobbins is back.."

"Since when?"

"Since last night. Anyway, I didn't want to leave her there. She doesn't need to be part of their rows. So she's over at Mary Ann's, happy as a clam. Oh, that doesn't look good," he said, pointing his chin toward the water and tandum canoes struggling offshore.

"Better than it did," said Louisa. "I thought for sure they'd both going under when Mr. Butler tried hitching their painter to his stern."

David watched for a moment as Butler and Jives hauled hard on their paddles, dragging in a nearly swamped canoe—the Joneses, someone confirmed. Faces pinched and strained, fingers white-knuckled on the gunwales, mother and father spent what little strength they had tyring to comfort their children.

"They've taken on a boatload of water!" called Mr. Butler when he reached fifty yards out. Five feet out, David and two others plunged into the ocean water to wade past Butler and Jives to angle in the half-submerged dugout...and the distressed Jones family. Butler and Jives managed to beach their own canoe and then splattered over to help, all five men hard pressed to nose the nearly submerged dugout onto the shingle, seawater sloshing. It ground to a stop, stern swinging, tipped sideways and dumped water over the gunwales. Mrs. Jones let out a startled scream, baby crying. Butler and Jives fell backwards onto the sand, so played out they couldn't get up. Mr. Jones, with the last of his energy, flung himself free of the canoe and tried to haul the canoe farther up onto the beach, but fell. He lay panting and shivering on the wet sand. "Get my wife, my poor children," he begged, holding his chest, and blinking his eyes..

Mr. Bettman already had Mrs. Jones out of the watery, tippy canoe and was carrying her, a tiny woman in shock, up to the tideline. David and Frank Matthias were dragging the canoe onto the beach, easier now that most of the water had drained, while Louisa's uncle, Hugh Latimer, side-stepped alongside, waiting just long enough for the canoe to clear the water before plucking up six-year-old Johnny King and his four-and-a-half-year-old half sister, both children blue and shivering and soaking wet, Olivia wailing. Louisa reached down to get two-year-old Percival, but he was tied into a crate securely fastened to a thwart. She dropped to her knees and tore at the wet, swollen ties that held the boy, blue and violently shivering. He suddenly stopped crying and stared up at her, chin jumping, the blonde coils of his hair dripping seawater into his face. Emily's age. She blinked back hot, stinging tears. She must get him indoors before he caught his death, if he hadn't already.

"Let me help." Abigail Holgate squatted beside Louisa, and gratefully Louisa let the widow take over; though she too struggled. She finally got the knots loose and snatched up the boy, opening her coat around him and giving a short, quick squeal of shock when the frigid seawater went straight through to her skin. "I'll take him, Louisa dear. There's another canoe about to come in." She hustled over the shingle to his stricken mother just in time to break Lizzie Jones' fall before she landed in a faint on the seaweed.

"Hoy! I need some help over here!"

Louisa whirled. Two men and a woman, and apparently the other baby. Tom Russell, the sheriff, was trying to heave one of the men to his feet. His wife was pleading to the woman, still in the canoe, to hand over her infant. David had squatted beside the second man, sprawled on his stomach, one leg still caught in the canoe. "Bill is it?" he aked.

"Will. Will Brannan."

"Will, can you walk a couple hundred yards?"

"I don't know, I can't find my legs. Give me a hand and we'll see."

Louisa skirted around and dropped to her knees beside the Nancy Russell and the crazed woman whimpering "no, no. No, it's to late, she's dead, I tell you she's dead." Louisa reached in to feel for a pulse, horrified at how cold and wet the baby was. "She's alive! Quickly, you must give her to me, Mrs. Brannan. You must!"

"No!"

Without thinking, Louisa smacked Mrs. Brannan's face, hard. Startled, she reached to touch her cheek and Louisa, taking opportunity, seized the six-month-old infant and ran. Dear God, don't let this baby die! she prayed, frantically wrapping it with her heavy sweater and gasping, like Widow Holgate, from the cold. She burst through the cookhouse door. A chaotic scene. "Doc! Doc!"

And that's how the Brannans came to stay with Louisa and David, everyone crammed into their "inside" house. Not an unhappy arrangement, though the uncertain days passed slowly, everyone waiting for the return of Curley and Suwalth. As for Bonnie Brannan's recovery, everyone took turns sealing her in warmth and love, passing her from one loving embrace to another. No one even thought of the thermos. Dropped somewhere and gone.

SIGN UP FOR MY EXCLUSIVE MAILING LIST

Brenda@BrendaWilbee.com

saddlestitch | $15.95 USD

| 6x9

| 978-0-943777-24-5

| February 28, 2018