The Tinsy Winsy Rag,

your monthly connect to this writer's life - and

always something

free & fun.

Thank you!

You have successfully joined our subscriber list. Tinsy Winsy and I hope you will not be disappointed!

Your first newsletter will arrive next month. In the meantime, please enjoy the many things I offer subscribers for free - including a pdf of my latest book, Taming the Dragons. Click here. Thank you.

Blog Subjects

- Alaskan Life

- Christian Nationalism

- On Writing

- Self-Publishing

- Book Design

- Christmas

- Narcissa

- Memoir

- Sweetbriar Illustrated

- Taming the Dragons

- Skagway AK Etc

- Guidepost Devotionals

- Living With Ravens

- Inspirational

- Christianity

- Reflection

- History - Women

- History - Seattle

- History - Gold Rush

- History - Family

- Family

- Racism

- Sexual Assault

- Sexual Molestation

Recent Blogs

- Sackcloth and Ashes

- Why Deny Abuse in the Christian Community? PART I

- Giving FROM my Heart, Not Giving AWAY my Heart

- When the Bible is Weaponized

- The Call of the North: "B...bbbbbear."

Recommended Sites

• Fauzia Burke, Publicist• Jane Friedman, Marketing

• Laura Christianson, Platform

• Susy Flory, Memoir

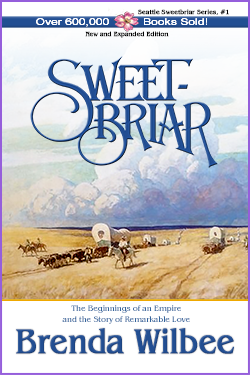

Sweetbriar #1 (out of print)

[NOTE: Not yet available. Please contact me—link below—to sign up for a notification notice.]

Cover Design:.Brenda Wilbee / byBRENDA Studio

........Interior Design:.Brenda Wilbee / byBRENDA Studio

Front Cover Images: "Covered Wagons" by N. C. Wyeth

..................................used by permission

.................Sketches:.© Brenda Wilbee

.......................ISBN: 978-0-943777-15-3

.....................PRICE: 15.95 / paperback

.

..

..

.

.

.

CHAPTER 1

new and expanded edition

It was a saying in those days that nothing must be take on the trail that was not worth a dollar a pound. I doubt that Louisa Boren was particular about the value per pound of the wall mirror that she wanted to take. Her elders objected on account of the extra weight and the risk of breakage. However...—Roberta Frye Watt in Four Wagons West

LOUISA TRIED HARD TO PRAY but the words came hard. She wasn’t accustomed to kneeling at her bed fully clothed, and thoughts of her plans kept getting in the way. It felt even stranger to be lying in bed with her shoes on, the blankets piled high. But she couldn’t run the risk of Ma coming in and finding her dressed. The blankets would have to stay.

Time passed slowly in the dark. This was her last night in Illinois; in the morning they were off to Oregon, the Promised Land. She listened to the familiar creaks and groans of John Denny’s farmhouse settling in for the night. In the distance she heard Uncle George’s dog bark, an annoying, ceaseless baying. She heard Jonah whine to be let out. “There you go, mutt,” Ma said. They were all going—except the oldest Denny brothers and the Latimers, Ma’s family.

Time passed slowly in the dark. This was her last night in Illinois; in the morning they were off to Oregon, the Promised Land. She listened to the familiar creaks and groans of John Denny’s farmhouse settling in for the night. In the distance she heard Uncle George’s dog bark, an annoying, ceaseless baying. She heard Jonah whine to be let out. “There you go, mutt,” Ma said. They were all going—except the oldest Denny brothers and the Latimers, Ma’s family.Louisa sighed and rolled over to stare absently at the armoire along the wall and found that her heart raced just thinking of everything she had to do. Carefully she went through her plans, all the while picturing her mirror on the wall downstairs at the foot of the steps. First thing in the morning the mirror was to go to Pamelia’s.

Or so the family had decreed.

The mirror was really her father’s, her real father’s, and Louisa loved it for that reason; but also because the mirror was so lovely to look at, framed in black walnut, its beveled glass ground and polished to perfection. Its only fault was its weight, much too heavy to go west. And the glass. But it had to go; the beautiful mirror was the only piece she had of her own Pa, the only tangible thing of lost memory.

The stairs complained under the weight as the rest of the family came up to bed. Louisa strained to catch the sound of David’s footsteps, but they were lost in the shuffle. She did hear his door shut across the hall from her, and then the easy, quiet banter of his voice as he exchanged good nights with three of his eight brothers—her stepbrothers.

David, of course, was the only reason she was going to Oregon at all, the only reason she was giving up her teaching and saying goodbye to Pamelia, her dearest friend on earth—and of course Grandmother and army of Latimer cousins. But is it worth it? Am I a stupid fool? Ever since David’s Pa, one of Illinois’ state legislators, had married her own Ma she’d been waiting for David Denny to take notice. But even after three years he still treated with her polite courtesy. But she had no other choice. David was going. And so would she.

Ma’s new baby, Loretta, fussed in the stillness. No one could have foreseen Ma with a baby at forty-five years old. Surprise, surprise, but not once had Louisa heard Ma (Sarah Latimer Boren Denny) complain about nursing an infant on the Oregon Trail or having to leave her elderly mother and nine siblings and three dozen or more nieces and nephews—and a perfectly good home to trek across the wilderness to an unknown land. But then why should Ma complain? Twenty-two years a widow; and having raised three children and run her own farm—she now had a fine husband in John Denny. Thirteen years older than her, a “weathered old horse” as he often described himself, he’d been over the moon with Loretta’s birth, his only daughter after eight sons. Ma and “Pa” had much to be happy about.

Louisa rolled onto her back to stare forlornly at the low attic ceiling. Ma had Pa; and she did not have David. An ambitious dream, she realized, given their age difference. On Saint Patrick’s Day last month he’d turned nineteen. In June, she’d be twenty-four. Twenty-four! No wonder he wouldn't consider her. An old spinster, a schoolmarm at that!

How depressing.

Quite suddenly she was aware of time passing. This was it, everyone in bed! She pushed back the covers and again knelt, this time to slip her hand beneath the feathered mattress. “Ah, good...,” she whispered unintentionally, startling herself. One by one and two or three at a time, she pulled several seed packets from beneath the mattress and began stuffing them into her dress pockets—surprises for her sister Mary Ann when they got to Oregon. Sweet Williams, sweet peas, heliotrope, marigolds, violets, alyssum, impatiens, carnations, sunflowers, hollyhocks. Yes, hollyhocks

The next thing to be done was pull the heavy armoire away from the wall. The monstrous but empty cupboard gave way easily now, and Louisa reached in behind, groping the dust balls for two small seashell jewelry boxes she’d hidden—next year’s Christmas gifts for her nieces, Mary Ann’s girls. Katy (six) and Nora (3) had expressed worry last Christmas that Santa Claus wouldn’t know where Oregon was, and so their stockings might be empty. Here they are. She scooted first one, then the other, fingers walking them toward her. Standing, wincing a little from a dizzy rush, she pushed the armoire back to the wall, no one the wiser.

She looked both ways before stepping into the narrow hallway. The coast was clear! Tiptoeing, she made her way to the stairs and began the dicey descent—pausing, heart thumping, with each creak. A slow go. But she eventually made it down without raising attention, mirror glimmering in the moonlight in front of her, right next to the front door. But first her coat. It hung in the hall along the stairwell, and with shaking fingers she dropped the jewelry boxes, hardly more than cubic inch, into the pockets. Now the mirror, she thought, shrugging into her coat.

For a moment she stood before the precious relic, gazing thoughtfully at her reflection, the dim halo of her raven-black hair and shadowed eyes, which were brown. Moonlight, splintering through the leaded glass kiddy-corner to the front door, caught the glimmer of her silver combs. A Christmas gift from David.

So pleased she’d been, elated in fact, but he’d spoiled it all by telling her that Grandmother had picked them out. For a while she hadn’t worn them, she was that disappointed. Yet he’d paid for them. That was something. And they were beautiful.

A noise overhead. Heart kicking her ribs, she darted back to the wall of coats and slid in under Ma’s black woolen coat. Nothing more happened. Furtively, she glanced up the stairs. Nothing. No one. She was about to lift the mirror free when in her head she heard Ma scolding: “You’ll take that mirror over to Pamelia’s first thing in the morning and no arguing. It’s bound to break and is far too heavy. You can’t expect the men to go to all the extra trouble. No, Liza, it’s been decided. Not another word.”

Well, it is going, she resolved, watching her ghostly reflection slant as she pulled the heavy mirror from the nail. Whether you like it or not. It’s my wedding present for David. Of this, however, she wasn’t certain. Still, it could never be a present if she didn’t take it.

Jonah barked when she stepped onto the porch. “Shh, it’s only me,” she cautioned. The air stung with a chill and Pa’s sheepdog padded toward her in the stiff grass. She shrugged the mirror tighter to her chest, then curled around it to help with the weight. “Want to come along?

Tail wagging, Jonah trotted alongside of her as she took the beaten trail to the covered wagons on the other side of the cherry trees lining the driveway into the farm—four distant white canopies ablaze in the moonlight. Pa’s was the first, and she hefted with some trouble the mirror up into the feed box Pa had nailed to the backboard and began climbing in herself.

"May I help you?”

Louisa gasped, wits startled right out of her, lost her balance; the ground spun around and up. But David was quick and managed to catch her before she landed unceremoniously on her backside.

"David!” she sputtered—surprised and stunned to find herself on her own two feet, caught in David’s tight embrace. His arms felt like hot bands of steel around her, strong and tight, and she stood embarrassingly conscious of his strength and closeness. Dizziness swept over her even as she fought to clear her senses and the putty in her knees. She’d heard people say that time could stop in moments like these, but she’d dismissed the expression as a very silly exaggeration. Yet time had stopped, David’s eyes boring into hers. Would she faint after all? But then David blinked and the spell was broken.

"What on earth— What— What are you doing here?” she finally stammered, finding her tongue at last.

"I am not.”

“You are.”

“You naughty girl,” he chided, giving a deliberate nod to the feed box and mirror glimmering in the moonlight. “Dear-dearie me, what will Ma say?”

She gasped in real alarm. Defiantly, she crossed her arms. “You know nothing of this,” she said sternly in a tone not unlike Ma’s. David surprised her by setting his hands squarely on her shoulders the way Pa often did when Ma was upset, and the unexpected and supportive gesture sent a thrill down her spine. When he learned in to whisper “I won’t breathe a word” she thought for a second she’d faint. Never could she have imagined that the intimacy of his voice in her ear could create such a dizzy spell, and she froze, caught off guard, not knowing what to do. But then he was gone, and she watched him duck between the cherry trees back toward the house. Dumfounded, she watched the long stride of his legs carry him all too quickly away.

“David!” she called, his absence a sudden and lonely thing. “Wait for me?”

He came back.

“I think I can do this myself, though,” she told him.

“I expect you can.”

Suddenly shy and self-conscious, and feeling the color rise in her cheeks when the scramble over the feed box proved to be a clumsy and undignified maneuver, she said, “Of course I can.”

So dark inside! All she could see of the wagon, a box four feet wide and fifteen feet long, was shadowed boxes, crates, barrels, and gunnysacks—the smell of potatoes and onions coming from somewhere. She waded in and, needing both arms to hold the mirror, she lost her balance once or twice, smacking a hip, then a knee. The floorboards dipped toward the wagon center, a specific design to keep everything from shifting in the journey. Finally, her trunk! She set aside the mirror to verify the nick on the brass lock, then lifted the lid and stared down into the contents. Everything would have to come out—her dresses, books, three sunbonnets already squashed. She piled them onto the floor in an untidy and teetering disarray.

Breathing a prayer of forgiveness for such willful disobedience—and not the least bit sorry—she wrapped the mirror between layers of an old comforter she’d made as a child and set it in, on edge, along the back wall of the trunk where it was less likely to break. Her books went in next, and copies of Godey’s Lady’s Magazine. Mary Ann had packed some along as well, for they hoped to decorate the walls of their new homes with the beautiful illustrations. One she particularly liked was one of a woman sitting on the moon. Others included the lovely floral ads for Pear’s Soap. The clothes she refolded and set back in, tucking in her brass candlesticks. David, she noticed, had turned to gaze at the stubbled wheat fields. What was he thinking? She could see the back of his head as she worked, as well as his shoulders, broad and muscular, and his toque—the one she’d knit him for Christmas with its array of colors. His brown hair was long and curling, sticking out from under the ribbed band. She disconnected the bag from her arm and brought out the seed packets and the two lovely boxes, and slipped them down into the clothing. The last thing to add was her white mull dress. A wedding dress. Again she glanced at David. Then shut the lid. Fait accompli.

Neither of them spoke until they crossed under the cherry trees. David said, “Sooner or later, you’re going to get caught with that mirror."

"By then it’ll be too late.”

“You’re always so pragmatic.”

David let the door shut in Jonah’s face. He whined and clawed at the door.

“Sorry, old boy,” said David, letting him in.

Louisa hung up her coat and headed for the stairwell. “Don’t tell anyone.”

“I said I wouldn’t.”

“David?”

“Yes?”

She realized she had nothing to say. “Never mind. Good night.” Halfway up the stairs, she whispered down, “Aren’t you coming up?”

“In a bit.”

He waited before feeling along the empty wall. When he found the bare nail, he grinned and closed his fist around the spike. What pluck from pretty Miss Louis Boren. But a sorry state of affairs it would be, he thought, if her mirror surfaced along the way. Pa—or Arthur—would certainly make her throw it out. The Oregon Trail was littered with such things.

The marriage of Arthur Denny and Mary Ann Boren in 1843 first brought them together. The subsequent marriage of Ma Latimer Boren and Pa Denny five years later, in 1848, united them as a blended family, and with the birth of their little Loretta Denny on Valentine’s Day in 1851, their blood lines mixed and crossed in the child and sister they all shared.

Three other children had been born. Arthur and Mary Ann had two: Lenora (Nora), 3 years old, and Catherine (Kate), 6 years old. Dobbins and his wife, Anna Kays, had a baby girl born just before Christmas: Gertrude, already shortened to Gerty.

The decision to uproot their family hadn’t been taken lightly, and had been a long time in the making. The Dennys knew it a serious undertaking; none were disillusioned as to the danger. But for years glowing reports from Cherry Grove families who’d already gone to the Oregon, each waxing on about Oregon’s gentle climate, improved health, and golden opportunities. Arthur suffered from fever and age, a debilitating disease that left him alternately hot, then cold, an annoying nuisance. By the fall of 1849, he’d seriously begun to consider taking Mary Ann and the girls.

And so all that long winter and into the spring of 1850, wind howling, snow piling up, the family gathered to enjoy Sunday dinners and to debate the issue. Over roast beef and potatoes and then coffee and pie, Katy and Nora put down for a nap, the old letters were brought out to read and reread. In time, Pa begrudgingly admitted opportunity in the politics. The Oregon was yet a territory; he could affect more good in the establishment of law rather than its amendment. The younger Denny men were more enthusiastic. They had nothing to keep them in Cherry Grove and adventure was always hard to resist. Louisa’s brother of course itched to go. The wilderness drew Dobbins like the Far North drew the Canadian geese each fall. The women, though, remained reluctant. Rich farmland, ripe opportunity, improved health—at what cost? What risk? What were the advantages if death found any one of them? Or all of them? In any number of a thousand ways?

Ma’s family, the Latimers, who’d founded the small community of Cherry Grove in central Illinois twenty years before, were not keen. Her mother at 74 years old had no desire to leave a place her husband had put on the map, and Ma’s nine siblings were equally invested: George with his Cherry Grove Seminary, William with his prosperous Black Angus ranch; Alexander his cherry orchard. Their disinterest reinforced her reluctance...and therefore her two daughters and daughter-in-law.

And so the debate stalled out while winter blizzards gave way to spring rain, daffodils, and primroses. When the tulips’ first colors began to show in May, Ma suddenly started to throw up. By the time the roses budded out in June, they all knew she was pregnant. And so was Anna—sick since February. They’d be taking two babies. An insane idea, and no one spoke further of the matter. Not even Arthur. But then August arrived and another letter, this one igniting a new whole new vision in Arthur.

He stopped by Ma and Pa’s that evening, shucked his dusty boots, and stepped into the parlor where his younger Denny brothers had gathered after supper, Pa in his chair, smoking his pipe and reading the Bible, a nightly routine. Ma stitched diapers. Louisa looked up from her cross-stitching. A hot night, windows open, and, despite the screens, flies everywhere. “I’ve made up my mind,” Arthur announced, pulling up a footstool. “Mary Ann and I, and the girls, are going to Oregon. With or without you. Here.” He leaned forward and thrust his letter into Pa’s hand, gave him a minute to read it. Then, to everyone else, he explained: “Wallace staked a homestead at the foot of a waterfall and installed a mill. Today he’s the goose that laid the golden egg. In just two years, he’s selling town lots and making money hand over fist with his real estate and the mill. I’m going out to see if I can’t do the same. I can build my own city. You can come if you want, Pa. I’d appreciated the help! David. James. Sam. Where’s Wiley?”

“Milking the cows.” Pa passed the letter to James, 27 years old.

“Think about it, Pa,” pushed Arthur. “If we go together, we can find a place no one’s ever been, take our pick of the land, and instead of farming our homesteads we can plat them, like Liberty Wallace there. We sell our lots to the newcomers. I have the surveying qualifications and start a store. New settlers are going to need everything from axes to sewing needles. David, we can go in together. Sam, James, we’re going to need attorneys and school teachers.” He grinned, eased to his feet, and went over to punch David in the shoulder. “Little brother, we stand to make a fortune.”

Pa pulled his pipe from his mouth long enough to say, “To build a real town, Son, you have to have a ready industry. Like a waterfall.”

“Plenty of waterfalls, Pa. It’s a big country, lots of opportunity. Think about it.”

He pulled on his boots.

In the end, it was the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law three weeks later that galvanized them all, even Anna, their most reluctant. A rich man’s daughter, Anna Kays Boren liked her tea parties and garden club, her piano, and concerts in Galesburg. Going to Oregon had seemed unfathomable to her. But the Fugitive Slave Law changed everything. Three miles north of their small community, the town of Galesburg stood center-point for Illinois’ Underground Railroad. The Borens and Dennys and all of the Latimers—easily half the county—had never been adverse to helping runaway slaves on their way north or dropping extra money into the collection plate for station agents who needed it. In Cherry Grove and on surrounding farms, quilts hung on porch railings and backyard clotheslines—signal of sanctuary in plain sight.

It was Sam, a reporter for the Galesburg Gazette (while apprenticing in law), who brought home a September paper outlining the galling gist of the Act. Grim faced, Pa didn’t speak for a long time after reading it. Everyone waited. Finally he stood and began pacing, hands behind his back, rattling the newspaper in agitation. The women—busy putting dinner on the table—exchanged anxious glances. “I won’t stand for this!” he finally erupted; startling Louisa and making her drop a fork. John Denny was not a man prone to temper. “This onerous bill allows Southern slave catchers, a particularly heinous breed of men, to storm our homes at will and without a warrant. Worse, it requires that we all— Wait, I’ll read it,” he huffed, taking the paper over to the window. “Here it is. ‘Furthermore, this bill’—and I quote—‘demands all U.S. citizens to aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution of this law.’ We must ‘aid and assist,’” he fumed, “these sons of the devil in their unholy crusade.”

David sucked in his breath.

Louisa put down her cross-stitch.

Ma made that cluck in her throat, and the brothers shifted in their chairs.

"And if we refuse,” continued Pa, “we are to be arrested.” He tossed the paper to David and began pulling on his hair, pacing again.

“It’s even worse,” put in Sam, having already read the article before bringing it home. “Slave traders are headed North like hornets, and intend to snatch free Negros off the street and sell them South for a stinging profit.”

“Sam, don’t say so!” burst out Louisa, aghast.

“It is so. They have no rights, free or slave, Louisa. They’re not entitled to an attorney. And the commissioners who handle these cases will get paid three times the money for sending a person South than not.”

She went back into the kitchen, too upset to think straight, and when she thought of Jasmine she just made it to the sink.

A week later Sam reported in the Gazette that Reverend Gordon over in Montmouth had been arrested. Four slave catchers had kicked in his door without so much as a knock. When he refused their entrance, one ran for the sheriff, demanding reinforcements and enforcement of the new law, while the other three pushed aside the reverend and ransacked his home, terrorizing his wife and children—at one point holding a gun to his wife’s head. No slave was found, but the sheriff, himself a station agent, had no choice when he arrived but to jail the reverend.

“Welcome to the Fugitive Slave Act,” Sam Denny concluded his article. “We no longer enjoy the sanctity of home and hearth.”

“I’ll not serve the devil,” announced Pa, soon as he got wind of it. “I won’t. Sally,” he said to Louisa’s Ma, “best break the news to your mother in the morning.”

Anna Dobbins Latimer, just finishing her breakfast, invited Ma, Louisa, and Mary Ann into the dining room with its yellow paint and costly knick-knacks displayed behind glass. A tiny woman with a halo of soft white hair, she didn’t speak about the decision. She instead asked Martha, an 18-year-old cousin of Louisa’s who lived with her, to fetch some tea. “Have you decided on a name for the baby, Sally dear?” she asked.

“I believe we’ve settled on Loretta.”

“A lovely name...Loretta. Oh, I love it!” said Grandmother. “But if it’s a boy?”

Ma almost smiled. “Surely, Mother, you know John Denny refuses to entertain any boy names.”

“Eight sons, who can blame him.” They all burst out laughing.

They were on the front porch when Anna Latimer finally asked, “When do you leave?”

But Ma choked up. Louisa answered, “Early to mid-April.”

“If we leave then, it’ll give us three weeks to make the Missouri River—and spring grass on the other side. If we leave too early, there’ll be no forage for the horses. Leave any later, we’ll find snow in the mountains.”

“Then we have six months,” said Anna Latimer. “We can make the most of it. And consider God good for letting me welcome this great-granddaughter of mine before you leave. We are surely blessed, are we not?"

Louisa leaned in and kissed her adorable grandmother. Who would it be harder to say goodbye to, her—or Pamelia?

| SWEETBRIAR BOOKS |

Sweetbriar #1 (ebook) | Sweetbriar Bride #2 (ebook) | Sweetbriar Spring #3 (ebook) |

| Sweetbriar Summer #4 (ebook) | Sweetbriar Autumn #5 (ebook) | Sweetbriar Hope #6 (ebook) | |

| FICTION | Thetis Island (ebook) | Shipwreck! (ebook) | |

| NONFICTION | Taming The Dragons (BOOK) | Skagway: It's All About The Gold (BOOK) | |

If you'd like to know when the new edition of Sweetbriar is reissued, please sign up for my email list.

I do not give out addresses.

Brenda@BrendaWilbee.com